Let The Music Play

Author Steven Vass on how synths supercharged 80's R&B

In this issue:

Headliner An alternative history of synths in 80’s music 🎧

Revival Will we care for those who cared for us? 🎧

Aftershow Brian Cox looms over another dysfunctional family, how Asian youth movements fought back in 70’s Britain, the poster art of eternal dreamer Yves Uro, 500 years of Black British Music and the book I contributed to

Eh up, people!

An expanded audio edition from London Town on a style and period of music that’s very close to my body and soul.

When most people think of 80’s music with synths and drum machines, the usual electro-pop suspects come to mind: Kraftwerk, Moroder, Depeche Mode, Human League, Gary Numan, maybe Patrick Cowley.

What we should be talking about is how black musicians quietly – ok, maybe not so quietly – revolutionised popular culture through their adventures in R&B from the 70s into the 80s. They could be smooth and sophisticated, but the tracks made you tingle and move.

Glasgow-based journalist Steven Vass has achieved something significant with his book Let The Music Play, plotting a course through those decades and tracing the evolution of these sounds through the constellation of artists who invented them.

The level of research is encyclopaedic yet he’s managed to keep it breezy, capturing the thrill of hearing these records for the first time – minds being blown every week – as underground club culture broke into the mainstream.

I caught up with Steve a couple of months after this launch in Brixton to talk about: how he got into writing; reasons and reservations in doing the book; being inspired by Coming To America; giving flowers to Kashif and Paul Lawrence, Patrice Rushen, Cameo, Kleeer, Gwen Guthrie, Jam & Lewis and many more.

What the hell – flowers all around.

He also offers theories on what drew listeners and dancers to these synthesised sounds, why black artists weren’t given more credit as pioneers and the differences between the UK and US markets.

Expect a Questlove Supreme level of discourse plus a big bag of that boogie-street-soul type of thing. A bit of house too, of course. You will feel it all.

Questions, comments or abuse to @ amarofpatel ✌🏾

Home from Home: Journeys into Elderly Care

My 81-year-old father has been bouncing in and out of hospital more and more. He has a litany of ailments – from cataracts in his eyes to arthritis in his wrists and ulcers in his legs. The real issue is mobility at the moment. Losing balance and strength. In turn, confidence and independence.

We’re not sure why this is happening; perhaps the spinal consultant has the answers. I have come to stay with him for two weeks and it’s knocked me a little further off course than usual. It’s the timing: let’s just say, I’m out of sorts. This stage comes around sooner than we expect. His decline steepened after my mother and brother passed, that’s for sure.

Though we have been here before, meaning that he tends to recover and muddle along, it’s diminishing returns. There have been falls, despite having various adaptations at home. Many elderly people are waiting longer for those than they should.

I’m fearful for the future and wonder if I have the patience, empathy and forgiveness to bend enough to his flaws and frustrating ways. Then, after tense exchanges, to uncover what he truly desires beyond his asceticism and sacrifice.

Amid personal frustrations, there is a danger that his troubles become inconveniences in my life. That my attempts to offer help, to propose direct solutions to problems rather than procrastinating or complaining as he likes to do, are misconstrued as insensitivity or a lack of compassion.

Dad would never want to be a burden. In fact, not speaking his mind is part of the problem. Minimal fuss, minimal expense. Where next if he can’t take care of himself? Should I insist he live with me? Is he willing to spend the money to go to the right home if the NHS is unable to meet his expectations? And what the hell is happening with social care?

People are living longer – that should come as no surprise. The UK’s over-85 population is projected to double by 2045. But how many department heads and policymakers have grasped the scale of the health crisis just ahead?

In March, The Guardian reported that there are almost 500,000 on waiting lists for care in residential settings or at home, while the vacancy rate in adult social care is the second highest it has been since 2012-13.

Staff are overworked, underpaid and undervalued. Meanwhile, local authorities are reeling from severe central government funding cuts and are being held to ransom by independent providers. Some have even gone bankrupt.

These issues brought to mind a probing and very affecting podcast called Home From Home, which forces listeners to confront the reality of old age and the complexity of family ties. I wrote a reflection in 2021 – reads like it could have been yesterday.

It’s produced by Ad Infinitum, a Bristol-based international theatre company. Their mission is “to 'challenge, move and provoke” audiences by telling stories about people who are marginalised because of their ethnicity, gender, sexuality or age, for instance.

Ad Infinitum’s co-artistic director Nir Paldi interviews three adult sons/daughters about their experiences of the care system, what it feels like to witness the deterioration of a parent, and the inner/outer conflicts that arise. These conversations are heightened by an evocative sound bed designed by Jennifer Bell, who also produced the podcast.

Each story draws you into the gravitational pull of its emotion. In episode one, Paul despairs at how his father can’t take any comfort from his staunch Catholic faith in his time of need as he languishes in a home he hates, riddled by Parkinson’s. Then there’s Cathy in part three, seeing her mother withdrawing from interactions with co-residents, for fear of experiencing another bereavement.

The most vociferous interviewee is Lizzie, a psychotherapist whose mum suffered a stroke and spent a month in a neurological unit. Lizzie’s sisters and their partners were keen that her mum be transferred to a care home but Lizzie knew she would hate it (having lived in the country, loved the outdoors and appreciated aesthetics). The homes Lizzie visited were very poor.

The debate opened up deep-seated differences in the family. Unresolved sibling rivalries playing out in the absence of the matriarch… Ultimately futile as her mother ended up in a home, which stunted her rehabilitation progress as she immobilised herself in protest.

Lizzie’s attitude is that quality of life is everything at this stage, even if you encounter risks along the way. You have to consider the social, psychological and spiritual implications of these decisions.

That’s why she would rather her mother embark on an arduous bucket-list trip to India, and possibly die while she’s enjoying herself, than fade away among strangers in a strange place.

Not only that – it is our responsibility to care for our elders and give them the most dignified and meaningful final chapter that we can, not abdicate that responsibility to an institution, as she explained to Paldi. This is the crux of it and will stay with me forever.

“I think that we are phobic as a society and as individuals,” says Lizzie. “We're phobic around death and dying. We can't handle it and so we stick our elderly away, unconsciously, because it's too threatening to see our own mortality in them.

“Then we have a situation where people will stay away from visiting their parents, or they'll do a tokenistic once a month or once every two months visit. Because it's so deeply confronting to see fragility and deterioration and dementia and Alzheimer's and so on.

“So they give it to the institutionalized parent and basically abdicate responsibility. So I think that the factors are extremely complex and I think it's too easy for us to do this, and I think it's a tragedy. Absolute tragedy.”

Season two is now available, featuring producer Keziah Wenham-Kenyon in conversation “with people that make up a fragment of the sprawling social fabric of the care system for older adults”.

You will hear about the experiences of elders of Caribbean heritage, those in the LGBT+ community and the ones living with dementia. What becomes clear is that the system needs more varied, nuanced and compassionate approaches to caring for underrepresented people from different cultures.

Keep that skin buttered, seen. Switch up the menu. Listen to them and then tweak the plan. More intergenerational gatherings too, like the project my former agency colleague Louise set up.

What are your experiences of elderly care? Any words of wisdom or suggestions you can offer? Drop a comment below.

Defiance

I was filled with immense pride while watching this three-part documentary about Asian Youth Movement (AYM) resistance in the late 1970s. It was a time of frequent National Front (NF) violence and vicious intimidation, as well as flagrant discrimination and brutality by the police. Peaceful protest could only get you so far.

Too often we had been portrayed as good immigrants – compliant, non-confrontational, docile even. “It was always a myth,” says Riz Ahmed, whose Left Handed Films produced Defiance.

It depends how far you push someone, right. My mum was diminutive, often sweet, but stood tall in the face of abusive customers in the corner shop. Even after someone put a knife to her throat.

Enraged by a series of tragedies including the murder of 18-year-old Gurdip Singh Chaggar in 1976, the fatal stabbing of textile worker Altab Ali near Brick Lane in 1978 and the suspected arson of the Khans’ home in Walthamstow in 1981 that claimed four lives, we see waves of young people rising up to defend their communities, families and businesses. They were prepared to go toe-to-toe.

Seeing Gurdip’s mother weeping at the funeral was almost too much to bear. As was the barely concealed prejudice of former DCS Gibson, who was in charge of the Khan case, continuing to peg a bereft father and talk out of his *ss about “honour killings”. You can tell that interviewee Zubia Darr is still haunted by the loss of her childhood friends in the fire.

The fact I and other children of immigrants can walk the streets of London alone with such freedom and in relative safety is down to the bravery and determination of members of organisations like Southall Youth Movement, which features heavily in the Channel 4 programme. (Respect to founder member Balraj Purewal and Suresh Grover of Southall Monitoring Group, who spoke with fierce articulation.)

But others were rising up as well, as Socialist Worker notes here, including the Indian Workers Association, which was instrumental in mobilising support for the protest against the NF’s attempted election meeting in 1979.

Article author Yuri Prasad also says that these movements were broader and more avowedly political than they appeared. The Sheffield Asian Youth Organisation coming to the aid of striking miners during the 1984-5 strike, for instance. Non-Asian sympathisers were also in the firing line as the death of teacher Blair Peach at an anti-Nazi League demonstration proved.

In episode three we learn about the Bradford 12, members of the United Black Youth League who heard rumours of an NF march heading their way and made petrol bombs in self-defence. They were never used but the police arrested them anyway. After a year-long campaign led by AYMs beyond Bradford, they were acquitted.

Interesting to note how several Asians used the word “black” to describe themselves in their pursuit of solidarity. An anachronism in our age of fragmented communities with multiples fissures around race, class and gender.

As Anandi Ramamurthy explained in her book Black Star: Asian Youth Movements, “Adopting a black political identity was to recognise the link in experiences between Rastafarians turned away from school because of their locks or Sikhs refused work in bakeries because of their turbans.

“It was an identity that was inclusive rather than exclusive and drew on a desire to create both local collectivities and global ones. In contrast to America, The Black Panther movement in Britain articulated the links between the struggles of Asians, Africans and Caribbeans in their conflict with the state over immigration laws, police victimisation and racism in the courts, arguing that the way forward was to agitate and organise rather than seeing the ballot box as a solution.”

This is our history. UK readers, I’m talking to you. But is it in the distant past? Flashback to seething far-right crowds by Trafalgar Square in 2020. Or a former Home Secretary inciting violence around Remembrance Day after calling pro-Palestinian demonstrations “hate marches”. As you can see, this island has still got issues.

Consider also that, post-Begum, the citizenship of anyone not born with white skin in this country is now more precarious. Stateless or otherwise. Ominous.

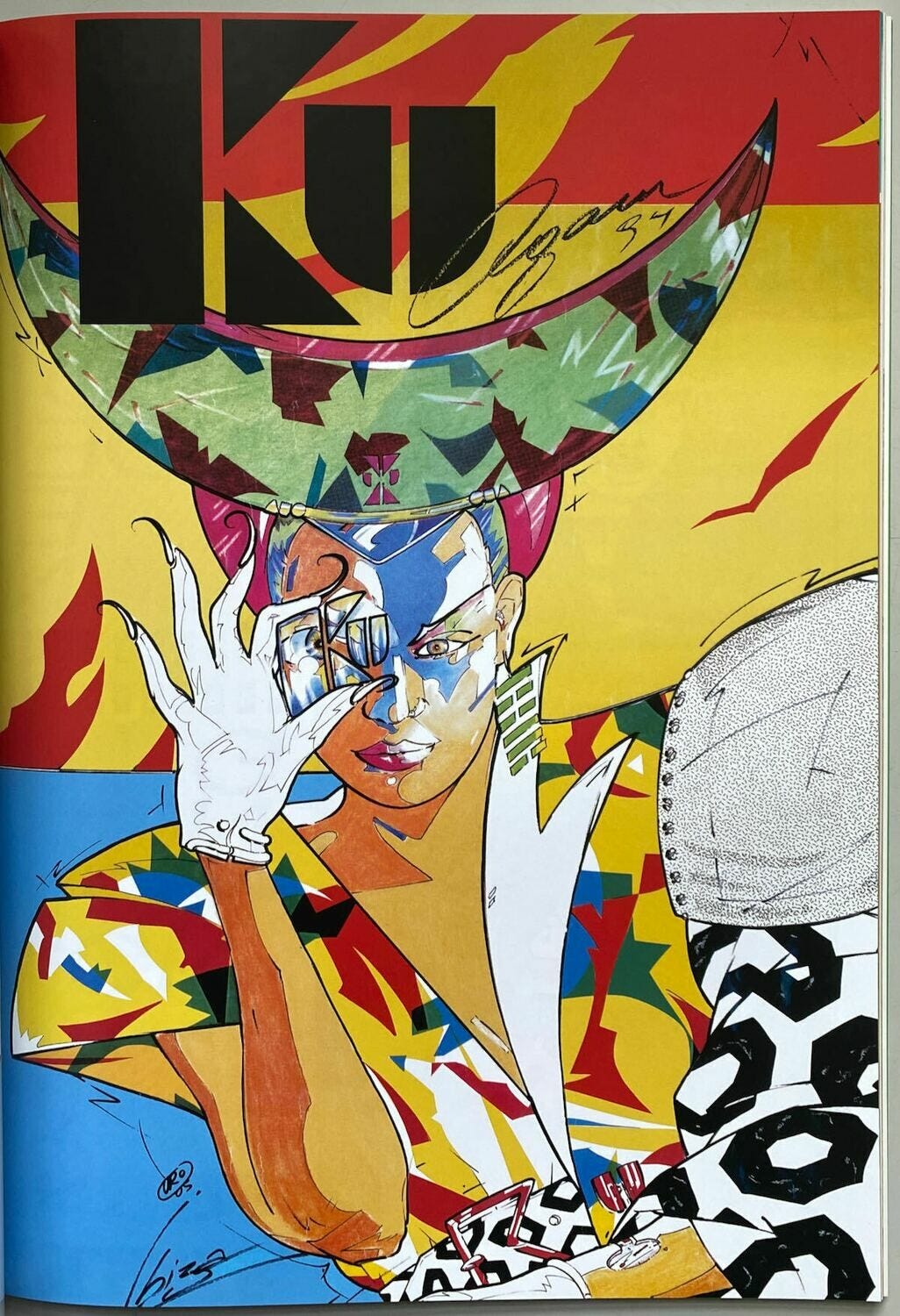

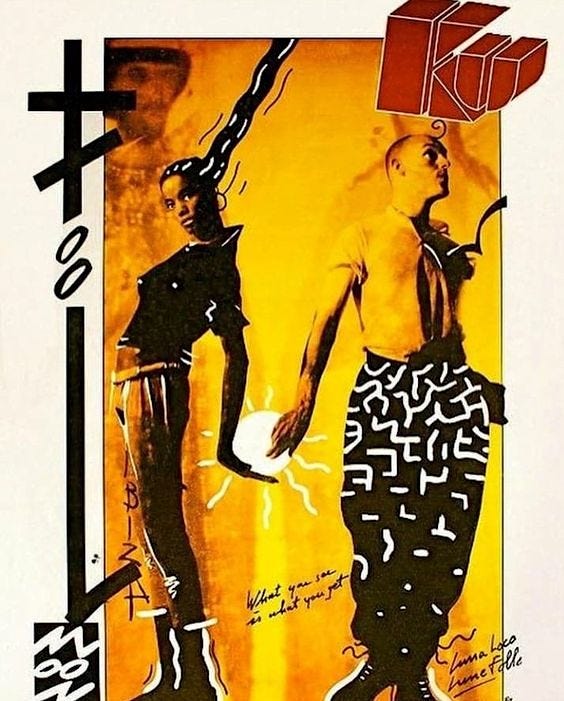

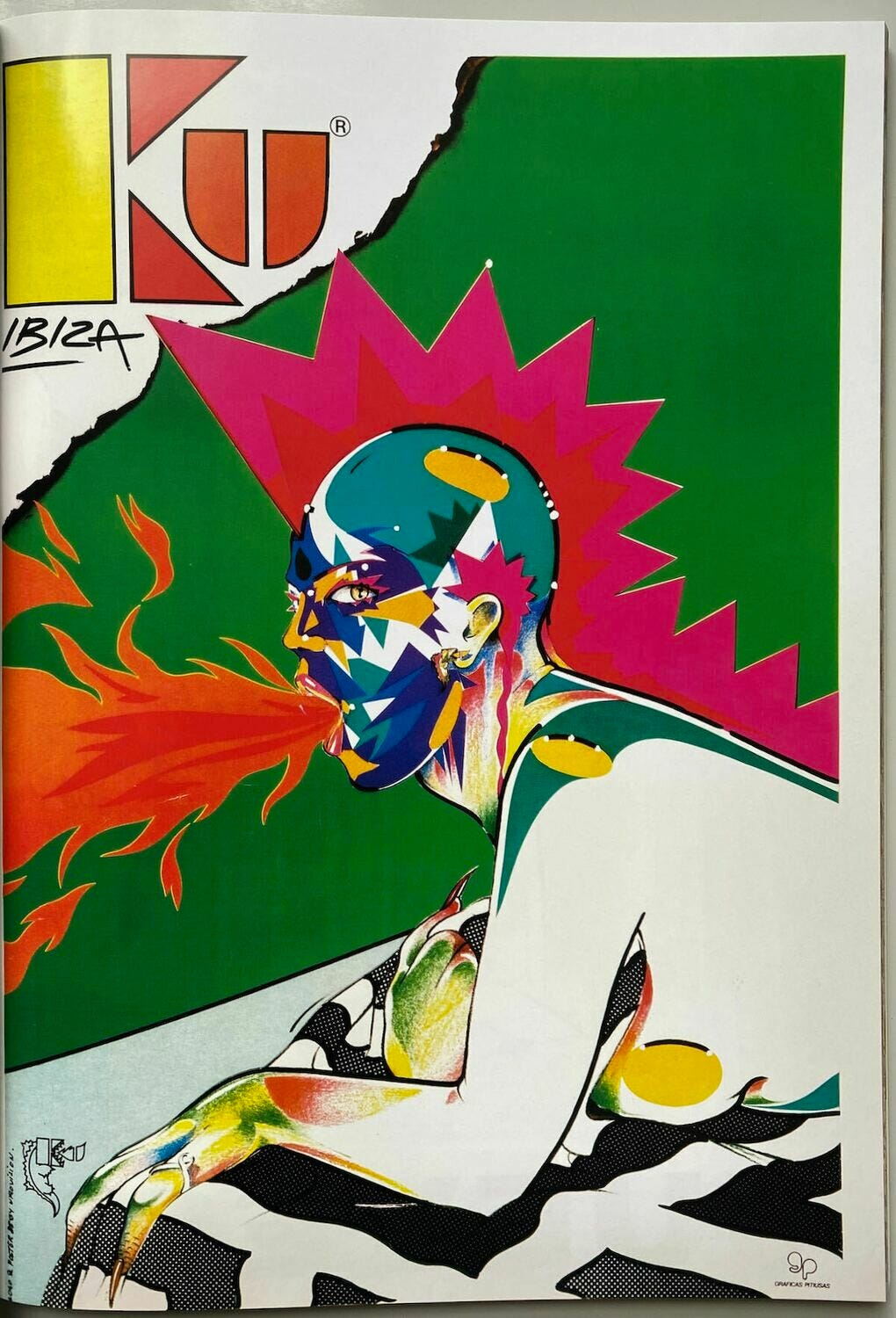

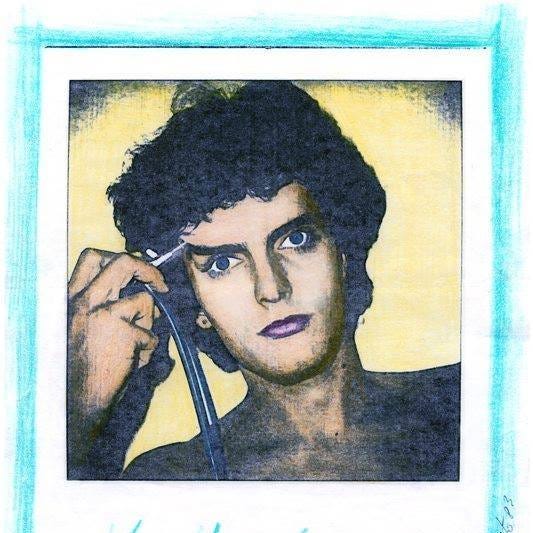

Uro Vision

Yves Uro must have been one of those special souls who could change your life in a moment. A free spirit and a true romantic, always yearning for escape and tempting you to follow. Someone who sensed so much beauty and wonder around him and could reflect it back in his work.

I first came across his poster art while visiting the Ibiza: Moments In Love installation at London’s ICA in 2013. A treasure trove of ephemera celebrating the White Isle as both pleasure island and spiritual sanctuary.

Yves' electrifying posters (sourced from the collections of 2manydjs David & Stephen Dewaele and Paul Byrne from Test Pressing among others) transported me from that boxy reading room to a bygone age on a bohemian isle.

Freedom was the bedrock of this place. Ibiza used to be a haven for liberal Spaniards during Franco's dictatorship, a new wave known as the Movida. The alternative community of freakniks of the 60s were followed by the thrillseekers of the 70s.

A place like Ku may have produced a pocket travel guide later on but the industry was still in its infancy. Clubs had yet to become "super-", drawing hordes of hedonists and commodifying the essence of the island.

If you had stumbled out of Ku or Amnesia in the 70s or 80s, you might be familiar with some of this poster art, perhaps even know who made it. You may even be one of the lucky revellers who peeled off a souvenir from the walls.

For those of us who didn't contemplate an escape to Ibiza until the 90s or beyond, Yves Uro is likely to be a mystery man. That's why the publication Uro Vision is such an event. "No books. No major gallery retrospectives. No modules taught in art colleges. And yet... one of the greatest of all poster artists… ever," says publisher Idea.

After sidestepping a potential career in engineering and military service, Yves left the greyness of northeastern France and the family straightjacket for a

sun-kissed isle where he could let his "quiet madness' run free, as sister Catherine writes in a poignant biographic introduction. She also contributes a travel diary to the second edition.

On Ibiza he co-founded Hay Tiempo, the island's first screen-printing workshop, complete with photography lab, later experimenting with four-colour and offset printing.

Between 1977 and 1990, Yves produced more than 400 freehand posters with kaleidoscopic airbrushing and painting (as well as perfume and T-shirts and interior design projects). Uro Vision features at least a quarter of them in all their glossy glory, together with family photos, early drawings, personal correspondence and other archive material.

Yves' work is enigmatic and allusory, mixing styles and casting spells. His imagery runs the gamut from otherworldly faces and lithe bodies to elephants, doves, smurfs and planets.

From an early age, he had a fascination with god, spirituality, higher powers, nature, the cosmos, space… A sensitivity in life that young Yves developed after almost losing his mother.

Catherine described him as "an eternal dreamer" and "avant-gardist" who sought refuge in his drawing and imagination. "You were born without a shell and you never managed to create one," she adds. "That allowed you to understand life differently and to have the unique sensibility that we see in your drawings."

Yves passed at 42, a singular artist who lit up the world with his flair and exuberant expression. Welcome a part of him into your home.

Long Day’s Journey Into Night

Eugene O’Neill is widely considered the great father of American theatre. This semi-autobiographical, day-in-the-life drama is his magnum opus. “A black farce about family friction and the difficulty of listening to people who are in the same family,” as director Jonathan Miller described it.

There is also an in-built mythology to it. O’Neill never intended for Long Day’s Journey Into Night to be performed. It should only be published 25 years after his death. His widow Carlotta, who inherited the rights, thought otherwise.

The core traits of the key players are drawn from O’Neill’s family, whether it’s the penny-pinching father or addict mother. In the story, the Tyrones have lost a son called Eugene, who was infected with measles by one of his brothers.

Another brother, Edmund, suffers from tuberculosis and uses writing as a “vacation from living”, as O’Neill once did. The play is like his exorcism, fusing stark realism, poetry and emotional honesty.

He said that his goal was “to get an audience to leave the theatre with an exultant feeling from seeing somebody on stage facing life, fighting against the eternal odds, not conquering but perhaps inevitably being conquered. The individual life is made significant just by the struggle.”

I’ve lost count of the number of iterations and adaptations over the years. The formidable list of actors who have performed it is a testament to how revered this material is. For starters, Miller worked with Jack Lemmon as James Tyrone and Kevin Spacey as his loafer son Jamie in 1986.

Take it back to 1962 and for Sidney Lumet’s film adaptation you had Katherine Hepburn as morphine-addicted mother Mary and a young Dean Stockwell playing her ill younger son Edmund. Sir Laurence Olivier and Constance Cummings shone at the National Theatre in 1971.

Jessica Lange won a Tony in 2016 for her turn as Mary, acting opposite Gabriel Byrne as her husband and Michael Shannon as Jamie. I could go on. Lange has even wrapped a big-screen version opposite Ed Harris. Perhaps that’s one way to make a 50’s production feel timeless – keep remaking it.

This time around, we have Brian Cox playing another irascible patriarch, albeit with fewer megalomaniacal overtures than Logan Roy. James is more capable of sorrow. A celebrated actor who pines for the limelight of yesteryear, rues bad career decisions and watches helplessly as his wife descends into morphine addiction.

He has his blind spots and prefers to rail against his sons, decrying their love of “degenerate” authors or how they’ve flouted the Catholic faith, than to see his own faults. Cox was the main reason I bought a ticket.

But I love Patricia Clarkson. It all began with The Station Agent. She never fails to connect with the sincerity in her eyes, no matter how small the role. Last night I watched Good Night, And Good Luck. In lesser hands, it could have been a forgettable support act to those big male actors on a journalistic crusade against McCarthy.

So often she manages to find a hint of inner conflict in opaque characters. Clarkson nails that closing monologue, which was my standout moment in the play. The way she perches on the edge of the stage only adds to the whimsy in her reminiscence. Mary may be strung out, living in the past, but it’s the only place she finds true happiness. Her pain is complex and nebulous. What is the morphine numbing, we wonder?

The core tension in this domestic tragedy is guilt vs blame, to which most of us in (dysfunctional) families can relate. Our willingness to see the extent to which we have a hand in our own failures. And how our blindness corrodes the souls of those around us.

O’Neill zooms in on this Connecticut family as they unravel over 12 hours. They live in the vicinity of one another, rarely together. John Lair puts it even better in his review. They are “satellites revolving around each other but never able to connect”. As the day darkens and the drink flows, we observe old wounds reopen and demons reveal themselves.

Clocking in at almost three hours, it’s a slow-burn, high-endurance experience that I couldn't fully appreciate from way up in the rafters of the Wyndham Theatre. No, you need to feel like you are in that living room, at that dinner table, watching eyes search for a glimmer of hope as fleeting levity fades to resignation, then dejection.

The cast also includes Daryl McCormack (Good Luck To You, Leo Grande) who portrays Jamie’s sodden, outcast demeanour with a touch of charisma on the road to oblivion. When he tells his kid brother, his Frankenstein, “I love you more than I hate you” but “I’ll do my damnedest to make you fail.” you’d better believe it.

Laurie Kynaston brings out the wispy dreamer in Edmund. Though frail from tuberculosis and considered an easily impressionable kid brother, he tends to have the best grasp of human nature and sees things that others can’t.

"The fog was where I wanted to be...Everything looked and sounded unreal. Nothing was what it is. That’s what I wanted – to be alone with myself in another world where truth is untrue and life can hide from itself."

And let’s not forget Louisa Harland (Derry Girls), who lifts the mood no end as the Tyrones’ quipping maid.

Beyond The Bassline – 500 Years of British Black Music

Get down to The British Library and dig into the roots and shoots of Black British Music. Yes 500 years. Travelling from the court of Henry VII to clubs and other sound communities across the land on myriad vibes and tempos.

To read some of the ignorant comments under early posts is confirmation that exhibitions like this are very necessary. Musicologists out there may be familiar with a few names. Pioneering composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, pianist Winifred Atwell (the first black artist to have a UK No 1), Cleo Laine, Lord Kitchener of Calypso, Claudia Jones (guiding spirit of Notting Hill Carnival).

A little later on … Jah Shaka, Soul II Soul, Eddy Grant, Cymande, Selector, Aswad, Neneh Cherry, Sade, Goldie, Skin from Skunk Anansie, Ms Dynamite, Wiley, Dizzee, Stormzy, 2024 Mercury Music Prize winners Ezra Collective. On and on.

They are the standard bearers of something greater. The stars that managed to stay in the sky long enough to catch the light or to be found by curious voyagers from another time and space.

This is not a definitive history. It’s fuel for an ongoing conversation about the value of Black British music as both a container of lived experience and a catalyst for a culture that we can all contribute to and support. A conversation that will continue across the UK, in libraries through the Living Knowledge Network, forums and feeds.

I liked what lead curator Dr Aleema Gray said at the preview evening, that this exhibition is at the intersection of many narratives. Where different perspectives, experiences and histories overlap is where, I think, we get the most truthful and meaningful representation of what came to be. Why these moments mattered and why they will endure.

But only if there is sufficient investment in research, documenting at a local level. Filming, photography, interviewing and collecting oral histories, then backing it all up.

Props to Aleema and guest curator Dr Mykaell Riley. Give yourself at least a couple of hours to immerse yourself. Find your own place among the artists, genres, records and scenes through the years.

PS Look out for the accompanying book I contributed to, which expands on the key themes and figures. It’s hefty. I set the record straight on cabaret star Leslie 'Hutch' Hutchinson – the biggest British entertainer of the inter-war years and certainly not just a gigolo.

Good curation! https://open.substack.com/pub/makepurethyheart/p/straight-up-wisdom-from-a-denim-jacket?r=1zorpg&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web

Cheers Paolo. Thanks for stopping by. Let me know if any moments stand out!