In this issue:

Headliner Why Sean Wang’s tale of teen strife struck a chord

Revival Nick Cave and Sean O’Hagan consider Faith, Hope & Carnage

Aftershow How to write sex scenes, why clubs will save us, the Oasisters and what is all the fuss about this reunion?

Being a teenager sucks, right? Isn’t that how most of us felt in the fire? If I close my eyes now and go back in time, I see myself in a body I don’t rate, in a place I can’t escape from (the shop/my head), receiving another lecture or “NO”. Too many chores, not enough pocket money.

It was all about studies, being sensible, obedient, abstinent. Trying a little too hard to fit in. In theory, such days should be carefree and spontaneous because there’s so little responsibility and more room to f*ck up. Perhaps if you were one of the lucky ones who got let off the leash, where adolescence became a wild run of role-plays to revel in.

To be in the minority is another hurdle as some of us try to find our place. I’ve written before about my experiences as a child of immigrants. How as a teenager “I could already feel my identity setting, my path preset”. Also, how there was a lack of South Asian role models to shake up the natural order of things.

“Where were the artists? The rebels and risktakers. The mavericks and mould-breakers we could follow. Someone to stoke our defiance, slap the need for approval out of us and say, go on, express yourselves. Bust out of that straightjacket of an acceptable profession, be it medicine, banking or law.”

To be cooked for, cared for, chauffeured, housed and protected is a world of privilege we take for granted at the time, like it’s a divine and universal right. As our world expands and paths cross, we discover just how cruel and unjust it could have been.

Only then do we develop a softer impression of the past and feel true gratitude. What is childhood if not a hard lesson in ‘you can’t always get what you want’? What you do get usually has a cost, which our parents tend to bear.

I still remember my mother stitching name tags to my prep school clothing late at night after another long day in the shop. Or my dad swamped in paperwork, forever the accountant, thinking how to scrimp and save. Always late to the dinner table, as if he was sated enough by his own prudence. What he should have been thinking about was a holiday, which we never went on.

Growing up in mid-90’s Brighton and Sussex wasn’t all bad. There was an abundance of time to idle away with friends, with no broadband or smartphones to distract us. Teen hours could feel like days – purgatory, sure, if you lived with a bully for a sibling – but it also brought contentment in the now.

Boys were being boys in boarding school – rude, silly, often hilarious. Awkward early encounters with girls at discos, where you could either be the man or a loser. It was high stakes on the cusp as we vaulted rights of passage, oh so in a hurry to grow up.

Alcohol was part of that. Continental stubby beers, if you must know. Sorry, I meant bière.

This was also possibly the last hurrah for mass communal moments in pop culture, outside of international football tournaments. Ones that felt sustainable anyway. Eager morning-after discourse on the latest episode of Twin Peaks or X-Files. The greatest era of action movies in the history of cinema, which you had to watch in the cinema or huddled around a VHS.

College corridors blasting out a mix of In Utero, Music For The Jilted Generation, Pulp Fiction OST, Definitely Maybe, Parklife, The Bends, Post, Odelay, Leftism, Maxinquaye, and a whole lot more. Minds being blown and tastes switching on a regular basis.

Some kids were ditching looks and hairstyles by the term. Each time was like a mini rebellion against standing still. A chance to begin again. Phases could be fun but peer pressure would make you feel so unsure of yourself. To fit in or stand out 😩 Whatever you do, don’t be a sheep.

It's this gauntlet of giddy highs and depressing lows that Sean Wang has captured with great sincerity and authenticity in Dìdi. His version of it, anyway. The R-rated movie may well bring you to tears with this volatile mix of icky comedy and emotional gravity. Seven years in the making, Wang’s debut film is inspired by his youth as a skate-obsessed Taiwanese American in Fremont, California. Or as he puts it, “an EMO kid in their feels”.

Izaac Wang plays middle-schooler Chris, also known as Dìdi (“little brother” in Mandarin and a term of endearment used by parents for their sons). He is quite socially awkward, embarrassed by his Taiwanese heritage and frequently clashes with both his older sister Vivian (Shirley Chen) and mother Chungsing (Joan Chen).

His father is always absent on business, which makes Chris feel like even more of an outsider because he’s living with three women. The third is his grandmother Nai Nai (Chang Li Hua) who is sweet but spends much of her time lecturing Chungsing on how to raise him. On top of all this, the kid’s got to deal with braces and acne. Urgh.

No wonder Chris feels at odds with the world. He’s so desperate to belong. As it’s 2008, arguably the beginning of the chronically online era, he tries to find and express himself through the digital tools of the day. We see him on MySpace, Facebook, AIM and YouTube where he begins to post early skate videos. One of his two obsessions.

The other is his crush Madi (Mahaela Park), who he tries to impress by saying his favourite film is the Mandy Moore classic A Walk To Remember and by stealing his sister’s Paramore T-shirt … among other items. Madi is intrigued and says he’s “cute for an Asian”, which tips him further into shame.

Chris is not a loner. He has a little gang: the more confident and boisterous Fahad (Raul Dial), Soup (Aaron Chang) and Hardeep (Tarnvir Kambo) who rarely miss an opportunity to poke fun. When he gets a chance to chat to Madi online, they start teasing him about her wanting his Wang (they call him “Wang Wang”, a third identity no less).

Chris falls in with an older group of skate kids who he blags into giving him a shot as their filmer. But they ask to see his ‘work’. A decisive moment is when he hovers over the delete button on YouTube before clearing out old clips of him clowning around with friends and family. He’s trying to erase the parts of himself he doesn’t like.

He lies about his mixed parentage so they call him “Half Asian Chris”. His old friend group is discarded and he drops out of their MySpace Top 8. He tells his family to stop calling him Dìdi. In about a week, Vivian will leave for college and he’ll (hopefully) never have to see her lizard-like “scaly-ass eczema skin” again. It’s rapid reinvention.

As you can probably guess, there are complications on multiple fronts and Dìdi reflects the messiness of adolescence in all its intensity and complexity. And within that flux, how easy it is for someone’s culture to be a source of embarrassment instead of pride.

We see this play out in obvious ways, like Madi’s backhanded compliment, and more subtle ones. For example, Chris not asking the older boys to take off their shoes when they come over, which the camera lingers on. He’s code-switching from another embarrassing Asian custom (which it isn’t, really). Then he ushers his mother out of his bedroom in such a brusque manner when she’s just being polite to his new friends.

Izaac Wang is very good at lashing out. He summons rage and frustration at will. But then he can fully embody his character’s sense of isolation in banal moments, whether he’s gazing out of a window or looking up from his bed.

It’s not all doom and gloom. Watch him beam for a few seconds as he tears around Fremont with his new gang or gets in on a prank. His range is incredible. This from a (then) 14 year old who had only ever done comedic roles before Dìdi.

Sean Wang – whose inspirations range from 400 Blows and Stand By Me to Superbad, Boyhood and Ladybird – says family isn’t prevalent enough in coming-of-age tales. Hence the importance of Joan Chen’s role in this film. Keep an eye on the Best Supporting Actress category next March.

Chungsing is a housewife having to raise two teens on her own. But before she was a mother and spouse, she was her own person with hopes and dreams. Chungsing loves to paint and aspires to be an artist but few recognise her talent except one of the older skate crew.

In a very moving conversation with Chris she shares her disappointment at how “ordinary” her life turned out to be and it almost broke me.

To be of a certain generation is to forsake everything for your children. But to put security and survival before self-discovery doesn’t mean you never had a passion. I know my mother felt that way about radiography, travel, style and fashion…

Spending 20-plus years grafting in a shop and then becoming housebound with an ailing body was not part of her plan. There were frequent tears in a strained marriage where she had little agency or independence.

Looking back, I wonder how much sadness and disappointment were masked as she languished in that kitchen day and night. Her daily existence mapped to a routine of medication, meal times and soaps. To what extent just one tantrum would trigger some quarrel with the past.

How easy it is to misconstrue loving and caring as nagging or meddling when we’re younger. The cultural and generational gap is hard to bridge. We can’t quite understand each other when our perception of the potential ways of being and succeeding is so different.

As an immigrant with two American children, who has played many mothers, Chen understands this well. “We as parents never feel like what we’ve done is enough. Your love is so strong that anything you do never measures up,” she says.

Her scenes with Izaac Wang are among the most endearing in Dìdi, whether it’s the sharp contrast in eating habits in McDonald’s or that excruciating car ride home after Chris gets in trouble. Can you believe that was their first moment together on camera?

When it comes to Chris’ relationship with Vivian, I can relate to them butting heads. The threats to put bodily fluids in each other’s toiletries, less so. There was a similar age gap between my older brother and I. We were also living on top of each other, agitated by our boredom and stasis.

Like Chris and his sister, I think we loved each other but didn’t know how to show it at that age, which made their brief moments of tenderness on screen so resonant.

Nostalgia will only get you so far in a coming-of-age film. Sean Wang has performed a magic trick in making a period piece that feels hyperspecific yet universal. I mean the tagline is “For anyone who’s ever been a teenager” so he had to deliver, right, even for us 40-somethings.

The writer/director says the story is personal not autobiographical, but the ties to his own life are endless. Chris’ bedroom is his childhood bedroom in Fremont, complete with a Jack’s Mannequin sticker and posters for Underoath and pop-punks The Starting Line.

Songs by Sean’s favourite bands such as Hellogoodbye and Motion City Soundtrack feature in key scenes, the latter an original track for which he directed the music video. He made playlists of the time for several cast members to inform the personality of their characters.

On the music front, I must shout also out the score by Giosuè Greco. At its best, evoking the reverie and melancholy of teen life. Although ‘The Squirrel Story’ is a whole other situation I won’t spoil for you.

Nai Nai, who you may have seen in Wang’s Oscar-nominated short, is the fimmaker’s grandmother. That doc was one of several stepping stones to this Sundance Audience Award-winning feature.

The first Wang work I saw was 2021’s HAGS (Have A Good Summer), a charming combination of yearbook photography and illustration where Wang calls up old middle school friends to see how they’re getting on with “adulting”. So much of what they discuss is relatable, from fearing you’ve peaked too early to wondering why you haven’t figured it all out by now.

See also Still Here where he revisits his family’s roots in a Taiwan village and 3,000 Miles, a chronicle of a year away working in New York that combines voicemails from his mother with footage that he shot on his Sony A7sii.

Joan Chen asked Wang’s mother to record all her lines so she could channel the inspiration for her character. Casting also reflected his early life. “We didn’t create such a diverse cast just to be diverse,” he told Focus Features, “but because that is honestly the ethnic makeup of Fremont's population.”

The way digital media was used as a storytelling device feels fresh, even in the post-Searching age. How kids of teenage Sean’s era, and later, would invent their own text speak and tone. Construct a persona from a gallery of photos or jump online to learn how to kiss like a pro.

Shaky, grainy uploaded camcorder footage of tricks and mischief became so integral to the texture of this film. It’s how the director started out, inspired by the likes of Spike Jonze who made him realise you could do scrappy skate videos and $100m movies.

In 2017, Sean Wang set out to make something homegrown and heartfelt, for kids that looked like him who grew up on the internet. He set it in a place and time he knew best and packed it with as much impishness, hijinks, angst and alienation as he could. An extended, tight-knit family formed around his baby. What a gift to also be swept up in his story.

For technology and other reasons, the window for adolescence to be both an age of innocence and free experimentation is narrowing. There’s more pressure to do the right thing, say the right thing and so on. More ways to feel insecure and think one mistake is the end of the world.

Dìdi offers no neat resolution or closure at the end, even in 2008, which is true to life. It’s about the ride. These will be some of the worst days of a teenager’s life but also among the best. You’ve just got to make it through and grab as much joy as you can. Take or leave the rest.

Oh … and a message to any young ones out there. Go easy on yourself. Sh*t is gonna happen. A lot. But it will pass. And life will go on. You have not peaked.

How do you look back on these years?

When did you feel happiest and saddest?

What would you tell your teen self?

Faith, Hope & Carnage

A few weeks ago, Nick Cave appeared on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert to promote his new record Wild God. There was a flurry of press coverage after the musician once again spoke about difficult matters with great articulacy and care.

How in grief “we turn inwards” and there’s a “desire to wrap ourselves around the absence of the person we’ve lost, as if there’s some sort of nobility [in it]”. For Cave, who knows a thing or two about bereavement, that is a mistake and we must turn the other way around. “See that the world is full of people who have lost things. The vulnerable precarious nature of each of us. That is what we are.”

His comment about AI echoes the concerns of many artists, for whom capitalist greed and a collective lurch toward convenience pose an existential threat. “The creative experience is seen as an impediment on the road to the product itself.”

Don’t get me wrong, I appreciate Cave’s music. This rendition of ‘Jubilee Street’ is one of the best things I’ve ever heard. Seeing him live in Porto a few years ago was every inch the sacred communion I had anticipated. “There are few better at the business of possession and ecstatic release,” I wrote.

My one-time fellow Brightonian is more of an old-school orator, which is what makes Faith, Hope & Carnage so nourishing. The book is culled from a series of lockdown-era conversations with journalist Sean O’Hagan, who he has known for more than 30 years. Loyal readers of his weekly Red Hand Files will savour its scope and depth of inquiry.

“When O’Hagan presses him about songwriting and the purpose of music, Cave uses words such as salvation, absolution, forgiveness and healing. And with real intention. In the context of personal disappointment, catastrophe or devastation, art becomes a means of survival. In Cave’s hands, the song is an act of transformation or transference – a form of supplication, at times – a way to pick up the pieces and move beyond.

“Those are the stakes at play in his world, a life in which he has learned to live in uncertainty and by divine possibility. In that time he has gone from running on the burning intensity of youth and rebellion to a form of spiritual audacity or zeal as he puts it. Cave’s depth of faith, in both the religious and quasi-religious sense, is what makes him such a compelling and crucial artist. Perhaps it’s also what’s allowed him to withstand so much and still be alive to raw experience.”

Full review here.

How to write sex scenes – without making people cringe

Despite being neither a novelist nor a writer of sex scenes I was all over this discussion about the steamy craft. Steamy 😅 A popular word in British media during the 70s/80s. Kinda stuck – in my mind. Tina Turner had something to do with that.

Anyway… Kate Weinberg (There’s Nothing Wrong With Her), Monica Heisey (Really Good, Actually) and others question reader assumptions, trade scenes, talk desire and more. Two bits stood out. The first was about why readers might think the author’s fiction is real life. Or in Weinberg’s words, they can’t invent the sex they haven’t had.

“We live in a time where people are hysterically obsessed by what is ‘true’ and what is ‘untrue’,” explains Heisey. “There is a frenzy for authenticity, even as it becomes less possible… And people want access. Not just to your work. They want access to your insides.”

The second is the male writer’s perspective, offered by David Nicholls (One Day). He would rather create a fumbled and awkward moment than try to arouse and risk coming off as chilly, slangy or worse … obnoxious. “Straight male desire has a terrible history on the page,” he says. “It’s either predatory or feels male gaze-y.

So how do you redress that while being authentic to what men think and say?

“I think women at the moment can get away with some really straight objectification. Male authors, at least straight ones, risk sounding crudely lusty or just ‘off’, somehow…”

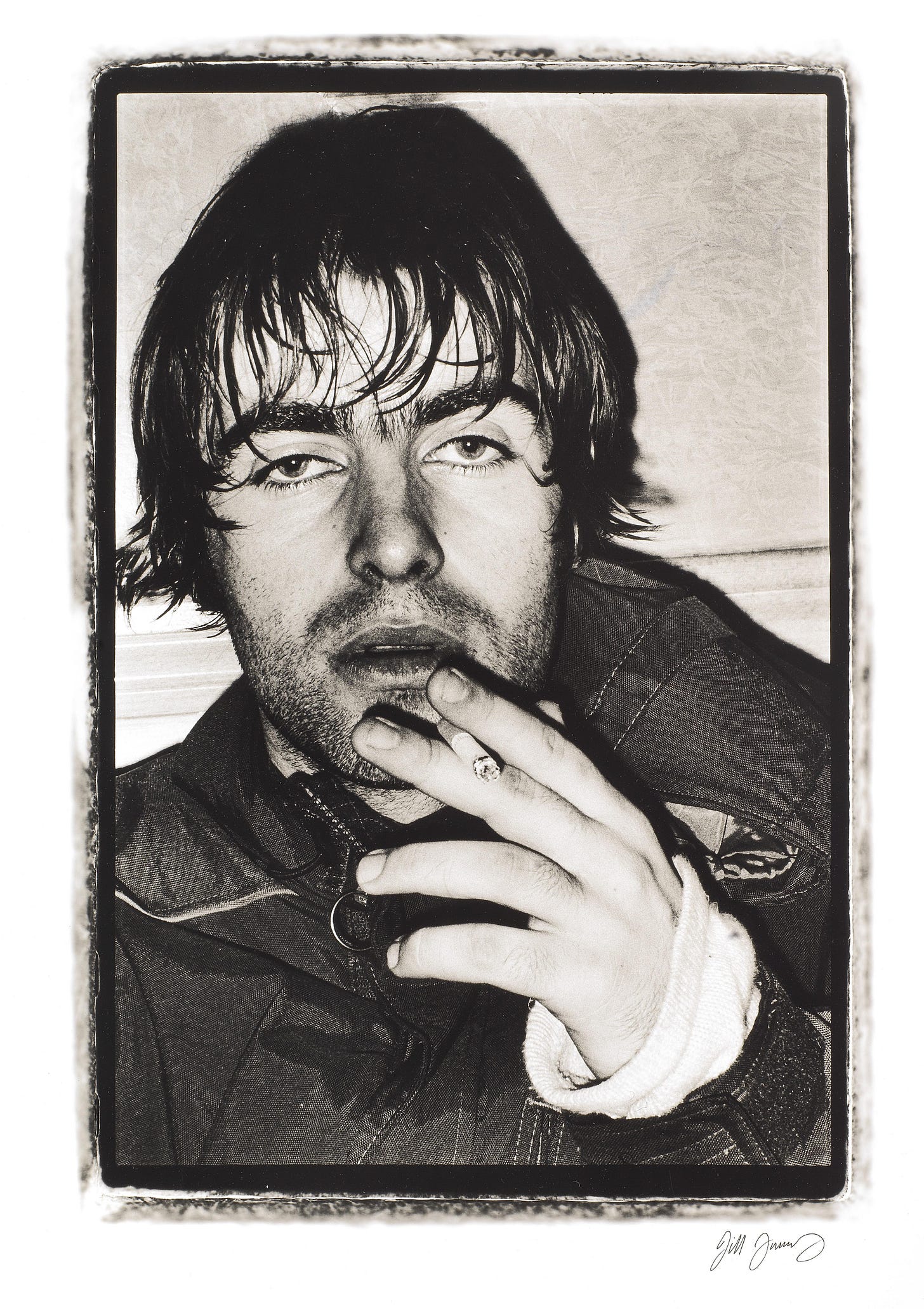

Oasisters: Meet Liam & Noel’s 21st Century Female Fan Army

Oasis are back together. You probably haven’t heard, eh.

Have you heard? It’s been a bit hush hush, I know.

As I type this, a friend is number 80,400 in the queue for tickets after four hours. [Correction: he’s been booted back to the start.]

Prices have doubled, trebled… Stupid money.

Hotels are laughing. Ticketmaster and Viagogo in a taking the piss contest. This seems at odds with the everyman spirit of the group. They have some say in how things roll out, yes? I’d like to think we are witnessing a national resurgence, an economic recovery that is going to trickle down to the estates. But, no.

The public’s reaction to their return has been … over the top? It’s not like Joni Mitchell or Led Zeppelin are going on a world tour or Hendrix is back from the dead. Is it even about them? Is there something else people are yearning for?

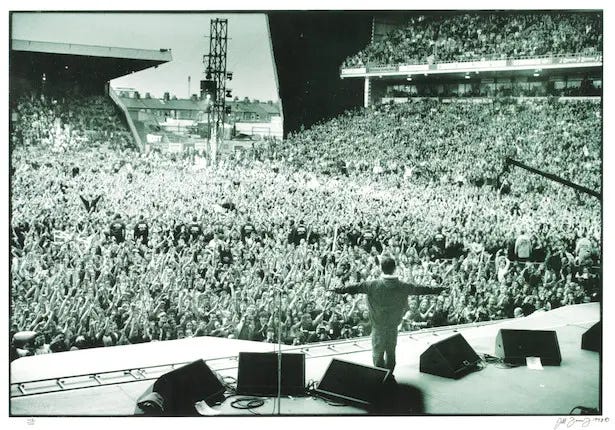

I’m not a hater. I grew up with this band (scroll to the top). It’s easy to dismiss Oasis as knock-off Beatles, loathe the Gallaghers as arrogant and ripe for caricature, ridicule them as Britpop dinosaurs. But for a period of 90s they made fans feel alive, untouchable, forever young.

The first album did sound like “an aeroplane taking off”, appearing right on time to liberate teenagers like me who craved music with more attitude. And who sought a live-and-direct band they could claim and come up with even if they weren’t from Manchester.

Oasis went out there with few plans or f*cks, racking up gigs and blasting anthems for us to sing pissed up, arms aloft, as we made light work of Noel’s simple melodies and catchy couplets and snarled like our Kid.

It was too early to interrogate the sound, deride it for its derivative nature or consider Noel’s theft. We were too in it. Throw in a great frontman with nuff swagger and a phenomenon was born.

My favourite Oasis memory is being on a rugby tour to Ireland in 1995, rolling around Cork and the surroundings as we sang along to a tape of What’s The Story (Morning Glory) that someone had copied straight after the album’s release. That “pub rock bollocks”, as Noel described it, worked well for lads on tour as it turned out 😂 We did it first, Lions.

This was the height of Oasis mania. I had my red tee with the logo emblazoned on the front. We spent one night in a hostel surrounded by these young girls “on heat” as a teacher described them 😳 They clocked the tee and spent the next however many hours calling me the “What’s the Story man”. I also had faintly ginger, cropped hair after a peroxide episode gone wrong, which only added to my infamy.

Oasis’ industry is not talked about enough. Every fan has their favourite B-side that should have been the A. Mine? ‘Acquiesce’, ‘Talk Tonight’, ‘Whatever’ or ‘It’s Good To Be Free’. Who else was giving us three good tracks arguably better than the single they accompanied?

I taped Live By The Sea and classic performances in front of wide-eyed crowds on The Word and The White Room. I even queued for Be Here Now outside HMV but by that point it was more bloated excess and “soulless pastiche” – as their number one critic Neil Kulkarni put it – than raw energy and palpable hunger.

That was him at his mildest. Listen to the full diatribe. May I suggest you read Neil’s well-reasoned demolition of the band. The venom in his vitriol, wow. I respect his points and conviction.

To like some of their songs is not to condone all that’s been said by the brothers in and out of the Loaded lads’ era. Too often, being outspoken has been worn as a badge of authenticity and realness when they should be held accountable for the dumb things they’ve said. They can both be very funny too – in a witty not nasty way. Here’s Noel on Liam, and Liam on saxophones and the dearth of rock n’roll stars.

It’s where we get into the band as cultural brand and how Oasis has come to represent a very reductive and regressive image of (working-class) Britishness where I begin to step away from the fanfare.

Whether you see merit in the music or not, the enduring connection Oasis has with its audience is undeniable. An audience that is expanding further than we realise, as author Anna Doble’s recent article for The Quietus explains.

I knew about Liam’s shows being popular with Gen Z, and how he’s very chirpy on Twitter. But read some of the quotes from young women and you realise how deeply they engage with the early music.

“Her favourite song is a Definitely Maybe-era track, ‘Listen Up’ which came out on the B-side of ‘Cigarettes And Alcohol’. For Bella, it is the tune that says it all. ‘As a 22-year-old woman, sometimes all you want to do is get away from it all and be left alone. The lyrics have a deeper meaning once you really get into that song and connect with it. The beautiful instrumental, Liam’s voice and the words Noel meant to express are a work of art. ‘Listen Up’ is also a great song to blast at 3am while looking up at the ceiling.’”

Will I be there? Definitely Maybe … not. If you are, enjoy the mass togetherness of it all, which is so rare these days. Sing along, whether you’re turning back the clock or living it right now. No gatekeeping here. You have paid for the privilege.

I might go and see a tribute band in some shite little pub instead. Now that’s proper raw and mad-fer-it.

Can we talk about something else now?

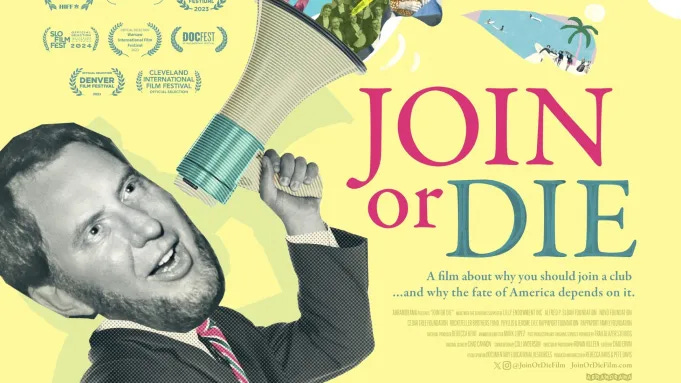

Join or Die

There’s a really important documentary making its way from the US that could help us fix democracy and tackle loneliness around the world. Join or Die expands on the work of political scientist Professor Robert Putnam who came to prominence in the late 90s with a study called Bowling Alone.

After rigorous research he found a link between a dramatic fall in membership of clubs and unions, and a steep decline in civic engagement between the 70s and 90s. For example, the number of times Americans attended a club meeting the previous year fell 50% in that period while the number of them taking a leadership role in any local organisation fell by a similar percentage.

Putnam asserted that IRL social networks have value or “social capital”. The key for him was reciprocity. In other words, if we all believe we’re in this together, the community prospers. At the time of the study, a major block on socialising was TV. Now it’s social media and hyperindividuality.

This decline has created a prevailing sense of distrust for one another (and institutions), which not only undermines social cohesion but also makes people more isolated. Approximately half of Americans say they feel lonely. In the UK, around a quarter of adults report feeling lonely always, often or some of the time in the UK.

Join or Die is more than a reminder of the continued importance of Putnam’s work. It’s a rallying cry. Co-director Rebecca Davis calls it an “organising tool” for civic rebuilding work. By making community screenings (sometimes to no more than groups of 15) a key part of the distribution strategy, the film embodies the very thing it espouses.

If you would like to host a screening, head here.

There’s more to say on this topic once I have spoken to the filmmakers.