Point Break: still the ultimate ride 🌊 🪂 🎭

Kathryn Bigelow's "wet western" is gung-ho, kinda macho and absurd. But it's still one of the best action movies ever made. A deep bromance for thrillseekers and Zen believers. What makes it special?

“An FBI agent goes undercover to catch a gang of surfers who may be bank robbers.”

This is the original logline for the most cherished action movie of my youth. Are you in, brah? I definitely was back in ‘91: a blue flame special who knew less than nothing about filmmaking, to paraphrase irate bureau director Harp (John C McGinley). Regardless, Point Break’s greatness was evident from the jump.

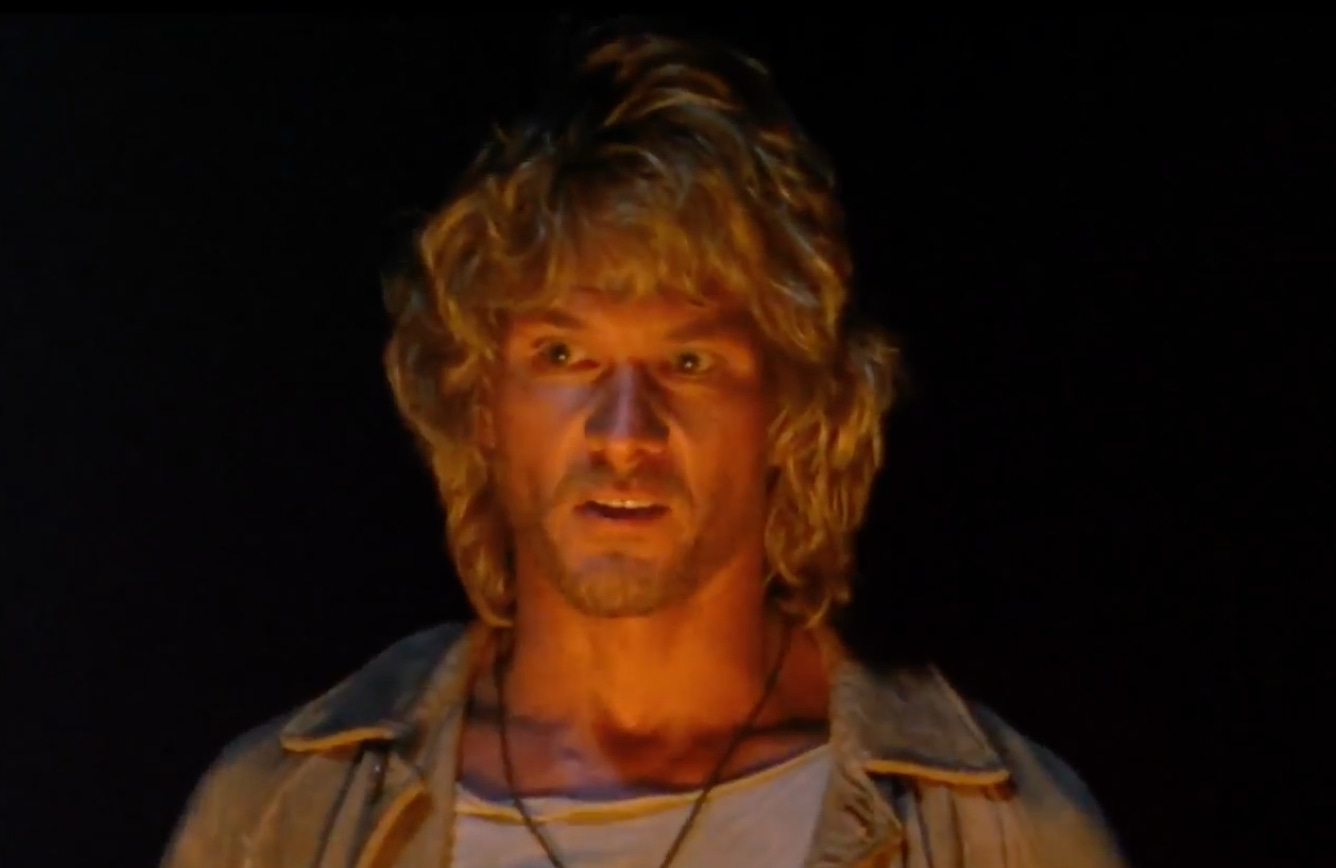

Those slow-motion glimpses of the mythic Bodhi (one of Patrick Swayze’s surf doubles, Matt Archbold) carving into the waves after its star names have converged. His movements appear to “gain a grace and fluidity not of this world”.

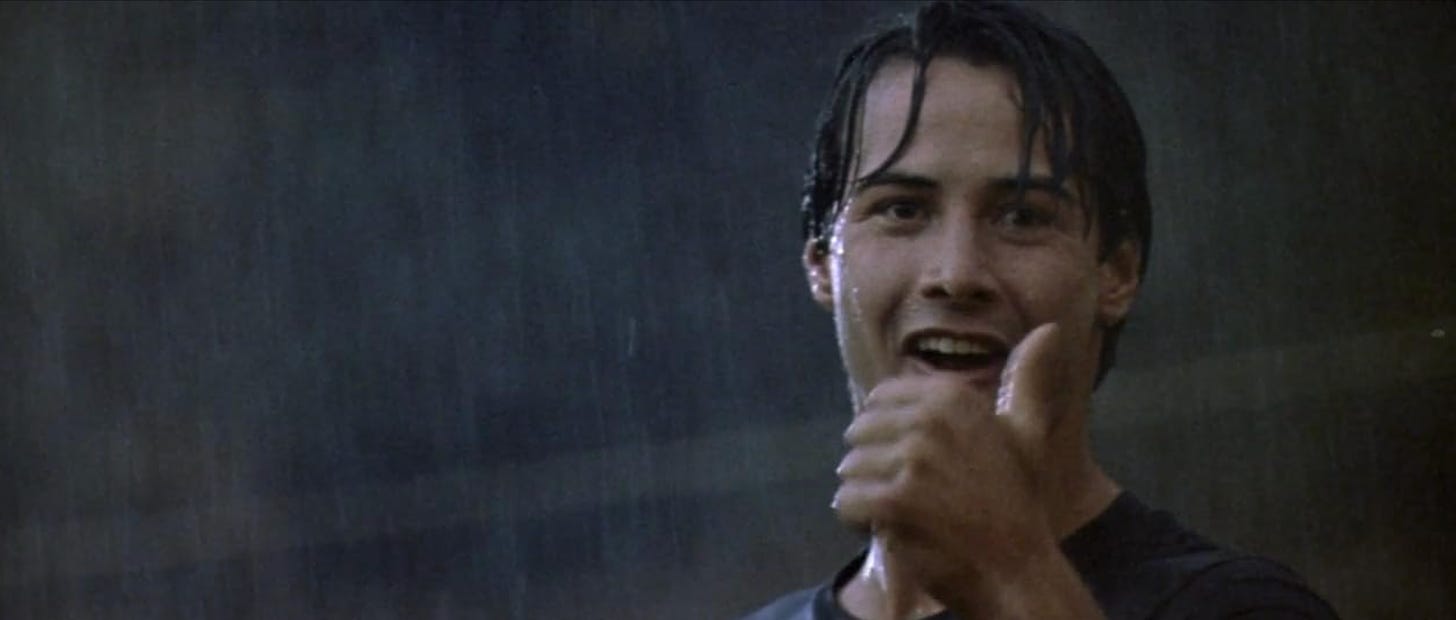

This is intercut with footage of buff, wet T-shirted recruit Johnny Utah (Keanu Reeves) blasting his way to 100 per cent on a training range as Mark Isham’s score swells to a gentle fanfare in the downpour.

Immediately, you feel anticipation at opposing forces coming together. Has there been a better intro to two lead characters in under three minutes?

Point Break’s box office return was quite modest, less than a quarter of Top Gun five years prior. On opening weekend, it generated less than a third of Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, which was popular that year.

Reviews at the time focused on the "preposterous" material that “invites parody”, its “flakiness” and how “it rides the crest of its own ludicrous wave with loopy abandon, continually threatening to wipe out”. And that’s a bad thing?

In the age of the blockbuster franchise and superhero fatigue, where derivative and diminishing returns are plundered from IP, here’s a thought. Perhaps that’s where you find original – on the brink of absurdity.

Over time, the film has evolved from a guilty pleasure, to a cult classic and now, depending on who you hang with, a masterpiece. (Only 79% on the Popcornmeter though. Everyone’s a critic.)

Whether it’s an unintentional comedy is beside the point. But the fact that Point Break and its quarterback punk spawned a riotous stage show, where punters could channel their inner Utah by booming “I am an efff-beee-eyyye agent” and other bombastic lines… Well, perhaps that’s the best punchline of all.

There have been plenty of heist films through the years, stories amid the waves and buddy cop movies. But to combine all three with a spitballer’s swagger and a devil-may-care attitude? Then imbue it with this duality of adrenalin and spirituality? Now that was fresh.

Kathryn Bigelow must take a lot of credit here, along with ex-husband James Cameron. The latter, whose seismic Terminator sequel came out within a week of Point Break in the US, was an executive producer who did a “significant amount of work” on the shooting script. And not only in subtle ways like changing the bank robbers from Dead Presidents to Ex-Presidents, which made its dissidence a little more acute at the dawn of the 90s.

According to original screenwriter Peter Iliff, who developed co-producer Rick King’s idea, Cameron turbocharged the action. He conceived the lawnmower scene at the bust and how Utah’s pursuit of Bodhi would play out in the air.

Did you know that, according to an earlier version of the screenplay, we were supposed to first meet Utah at an FBI simulation where he goes over the top? We might never have seen Keanu’s cheesy grin after he gets full marks on the range. That sets the tone for the whole movie in a way.

Bigelow was coming off films such as Near Dark, where cowboy Caleb (Adrian Pasdar) is ensnared by a gang of vampires whose acceptance he covets. While in the thriller Blue Steel, NYPD newbie Megan (Jamie Lee Curtis) becomes involved with the serial killer she is chasing on her first major case.

Both protagonists are quickly out of their depth and lured into murkier worlds. Bigelow would take this fascination with coming of age into even deeper, choppier waters on her next project.

Nowadays, she is well known as the first woman to win an Oscar for Best Director, but Bigelow comes from a conceptualist art background. She was a painter for whom film became an “interchange” of several ideas and interests. Bigelow studied with the likes of Susan Sontag and Miloš Forman. Time in the Art & Language Group also gave her “as critical a distance from the work as possible”.

Here we begin to understand her alt mindset on Point Break, turning what could have been a schlocky and charmless romp into a subversive yet propulsive spectacle. Instead of going with Charlie Sheen, Johnny Depp or Matthew Broderick as her action star – names mooted when Ridley Scott was attached to direct “Johnny Utah” in the late 80s (close one 😮💨) – she fought for one half of Bill & Ted.

Patrick Swayze was coming off the back of love stories such as Ghost and Dirty Dancing. He had kicked ass before in Road House but never played a villain. Of course, Bigelow didn’t see Bodhi like that and wanted to stress-test the bond between him and Utah. “It’s a little more complicated when your good guy is seduced by the darkness inside him and your villain is more of an anti-hero,” she said.

On paper, Bodhi is the rebel master to Utah’s naive apprentice. A free spirit looking for the ultimate ride. He could easily have come across as a huckster, an egomaniac or just full of sh*t. Swayze connected with, and built on, his character’s “wild man edge”, bringing a potent blend of the physical, intellectual and philosophical to his role. I’m howling at this description in Thrillist.

“Has any actor so fully embodied every New Age truth at once? Watching him in Point Break is a bit like listening to an Enya song, staring at a crystal, and doing one-armed pull-ups at the same damn time.”

Who else could make a thief so righteous and sell lines like this with such conviction?

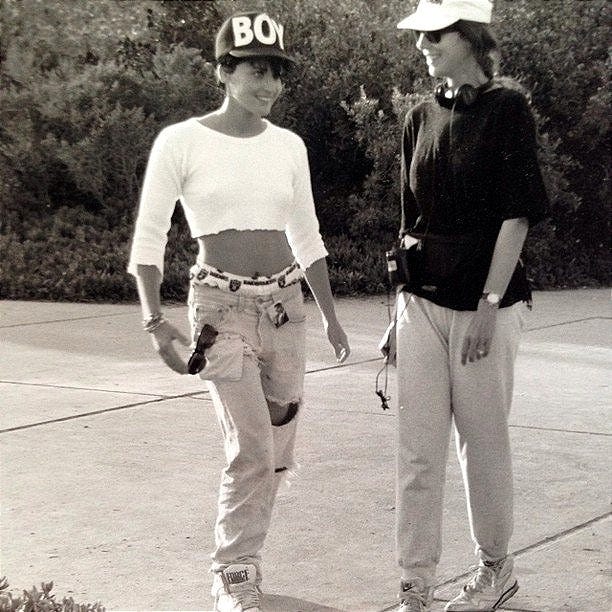

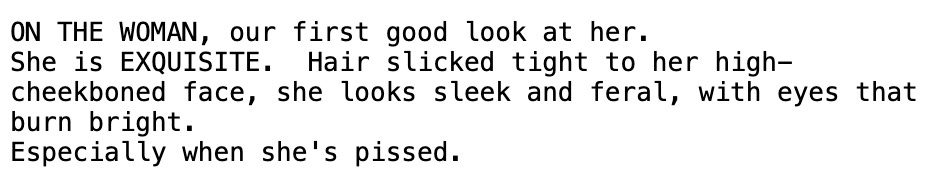

Tyler, Lori Petty’s character, was originally conceived as a “quintessential surf chick”. The California blond. Bigelow imagined her as more of an athletic and androgynous figure. Some might say with a “sardonic feminist edge”.

She does save Utah from drowning, teaches him to surf and rolls her eyes at the testosterone-fuelled chat about riding big waves and dying young. All that before half-time.

Here is our introduction to Tyler in an early version of the shooting script.

Petty is underused and, inevitably, becomes a ‘damsel in distress’. Otherwise, it is a decent runout in the early 90s manosphere. She made a big impression.

Bigelow has a gift for orchestrating visceral action sequences. McGinley was right when he said she made the on-foot chase between Bodhi and Utah as exciting as a car chase. It was captured on PogoCam by camera operator James Muro as they tore along backstreets, into backyards, through living rooms and over fences. “What excited me was how absolutely alive it made the frame,” said the director.

That’s why so much of what we see is for real. Bigelow was chasing that feeling. Many of the actors trained for nine months with Spyder Surfboards’ founder Dennis Jarvis. Petty had never been in the ocean before Point Break. The director pushed her actors out of their comfort zone.

Swayze, defying the insurance suits, skydived more than 50 times around shoots and blessed us with one epic backwards jump on camera. (“Adios Amigo!”) The action is almost always in service of the story and to explore the dynamic between the hotshot rookie and his anarchic mentor.

From the start, she liked how the worlds of these two men were in direct opposition to one another and saw action as a conduit to something more transcendent. “I have a desire to subvert genre and refine,” Bigelow has said. “Genre exists for that purpose. It’s a great interlocutor with the audience, a way in, a language they understand and that makes them comfortable.”

On the one hand, we get thrilling set pieces like Utah scrapping with the crystal meth surf gang, showing his competitive edge during a night-time ball game, the foot chase after Bodhi (who even throws a pitbull at him, kinda), the breakneck bank jobs, Utah hurtling through the sky without a parachute…

But there are also calmer, awestruck moments. For instance, when Utah manages to surf a wave in the dark, Bodhi telling him to “just feel what the wave is doing, accept its energy, get in sync, then charge with it”. It becomes a transformative moment.

Overwhelmed, Utah sits on his board by Tyler as the gentle swell of the twilight ocean shimmers in the background. The glee on his face is childlike. His rebirth has begun.

This scene resonated with me as a stressed-out teen. Everything felt like a school project. I was preoccupied with my studies and daunted by expectations. Years on, when anxiety and a to-do list threaten to pull me out of the moment, I call up this screen epiphany.

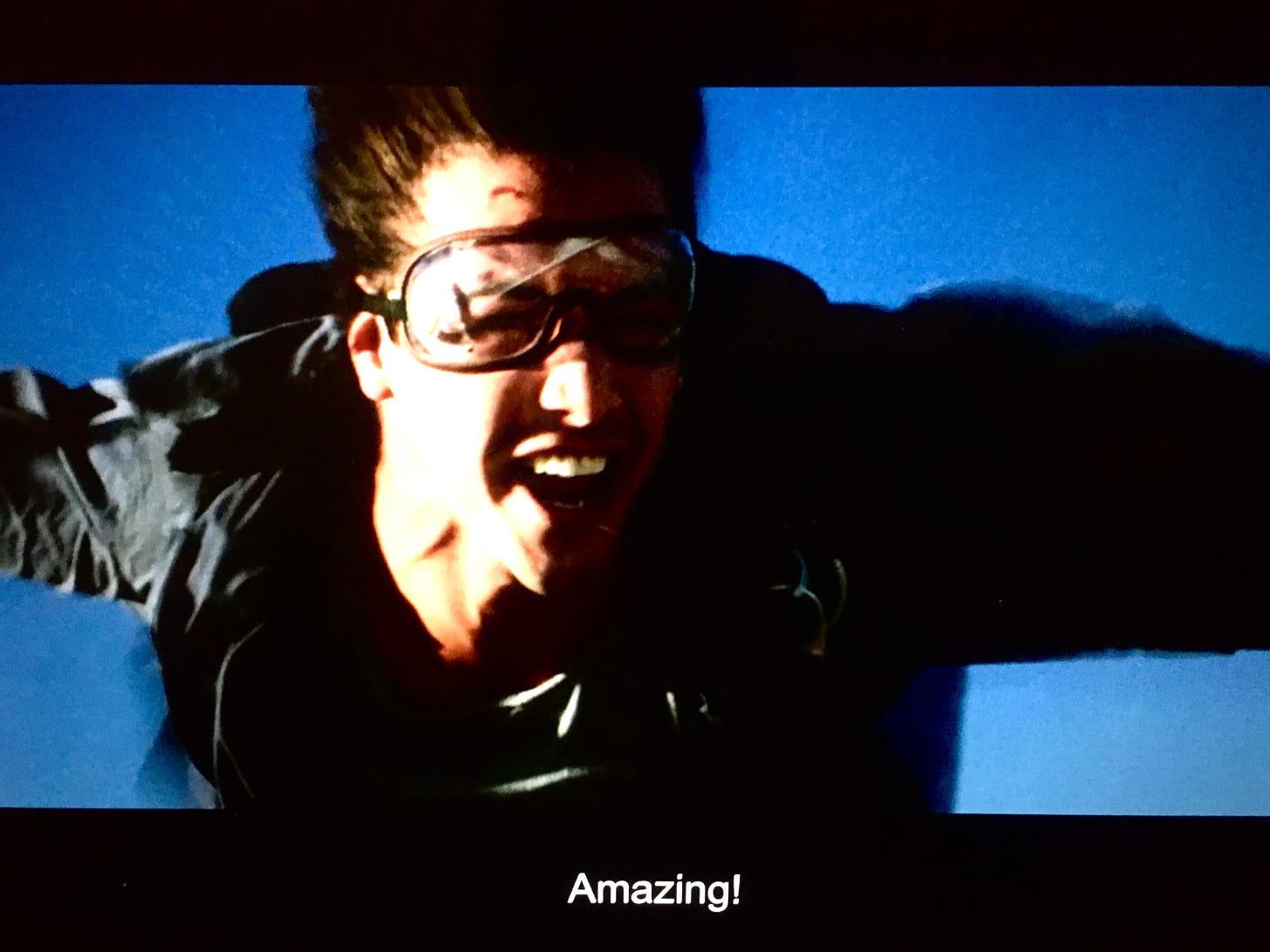

Even more liberating is Utah’s first skydive, another initiation at Bodhi’s behest. Utah knows his cover is blown. It’s getting tense up in the air and he thinks he might plunge to his death because of a dodgy parachute.

But as soon as he leaps out, hangs over the world and feels the sweet sensation of surrender, Utah forgets the job for an instant. They join hands and he becomes part of the brotherhood … until Bodhi pulls out that tape.

I, and many others, jumped out of a perfectly good airplane because of this movie. The balletic grace of an eagle-like Swayze was beyond inspirational.

However, Reeves’ elation was much easier to emulate at 12,000ft.

It’s the thrill of danger that Utah loves more than upholding the law. That’s what draws him to Bodhi and vice versa. Faced with the opportunity to shoot his man, Utah can’t do it (why, we’ll come back to).

It’s like Tyler says to him as the special agent becomes seduced by his chief suspect. “You got that kamikaze look, Johnny. I’ve seen it. Bodhi can smell it a mile away. He’ll take you to the edge … and past it.”

In the van, after Utah is coerced into being an accomplice on their next job, Bodhi bats away the FBI man’s call of duty, saying “We can exist on a different plane. We can make our own rules. Why be a servant to the law when you can be its master?”

Utah still has his own sense of right and wrong but this is the only way to save Tyler. On their last bank job of the summer, Bodhi breaks his own rule. Whether it’s his compulsion to always raise the stakes or pure greed, we don’t know. He goes for the vault and ends up killing an off-duty officer, while one of his crew dies in the shootout.

The resolution we seek in the final act is about more than cops vs robbers and Tyler’s welfare. The engine of this story is the complicated kinship between Utah and Bodhi. Who are these men to each other after the first flush of their bromance, post-betrayal and now in the stark light of morality?

Point Break picks up where Lethal Weapon let off in the previous decade in terms of examining affection between two men. But by placing them on opposite sides of the law and at different stages of their self-realisation, the conflict in this relationship becomes more nuanced and compelling.

For so long, the action hero had been cast in the bulletproof image of Schwarzenegger, Stallone and Willis. Hyper-masculine, wise-cracking, trigger-happy saviours. Islands of manliness. If they felt weakness or vulnerability, they rarely showed it.

We see Utah in states of change, which is exhilarating to him, but by the last quarter he’s not the cocky hotshot who strode into the office on day one. He is far less sure of himself. The catalyst is his frenemy who has a hold on Utah.

There has been a lot of saucy speculation about his attraction to Bodhi. Writers like Sam Reimer saw Utah “descending into a fully-fledged homoerotic reverie” the first time he lays eyes on him.

Others pinpoint the “intense stares” the two men share at the house party where Jimi Hendrix’s ‘If 6 Was 9’ is playing. Or Bodhi telling Utah, “I know you want me so bad it's like acid in your mouth,” before bailing out of the plane like the abrupt end to a meet-cute.

Shadows of guns become phallic, as do protruding boards in the water. There are complex shot-by-shot breakdowns of how Bigelow subtly conveys Utah’s yearning and softens the edges of masculinity. How “surfing, the ocean and Bodhi offer an entrance into the sensuous unknown” as Broey Deschanel puts it in her video essay.

Reimer reads a hell of a lot into a bare ass on screen, saying the “paused posterior now resembles a man waiting for intercourse” and Utah is “distracted and allured by the suspended image” 🤔

And how about the scene where Utah shoots a round into the sky after Bodhi escapes? Fans of Hot Fuzz will know where I’m going here.

I was raised in Brighton, hardly the land of Puritans. Relationships of multiple permutations have blossomed by the sea for decades and I’m very cool with it. Everyone is entitled to their own interpretation but I don’t think Bigelow was trying to make “the ultimate gay-subtext film”. Apologies if I am killing someone’s fantasy here.

That said, Swayze did want “to play it like a love story between two men” (which can be platonic, woah) and in Bigelow he found the perfect collaborator. As a woman in charge, she could take a step back from the machismo, he said, and by bringing “a deeper level of truth to it, wonderful things can happen”.

The climax on Bells Beach (actually Cannon Beach, Oregon) is still among the most poignant in action movies. There’s something rather poetic about how art imitated life. Both actors had been away filming other projects for several months before reuniting to reshoot the fight scene. Swayze on City of Joy and Reeves on Bill & Ted’s Bogus Journey.

Reeves had longer hair and a scruffier appearance, while Swayze was shorn of those incredible locks. (Sidebar: is hair the reason that remake flopped? Or is it because the 2015 version is a charmless, feature-length extreme sports ad?)

Anyway, back to 90’s Bells… You could imagine that Utah has gone off the rails and rejected authority in a big way, while Bodhi is a lone wolf without his pack and a fugitive trying to keep a low profile.

This version of Utah still wants to get his man, who is standing there defiant on the edge of the shoreline, fixed on the 50-Year Storm. His vision has come to pass. He waits for his set.

Their relationship is still built on rivalry and respect. If only his brother didn’t rob banks, perhaps they could surf off into the sunset together. But human beings are fallible and Cali’s flaxen Bodhisattva is no different.

After their scrap, Bodhi appeals to the surfer in Utah, a part he nurtured in the place “where you find yourself and you lose yourself”. Rather than confine this modern savage to a cage, Utah grants his friend and mentor an honourable death, which King and Iliff always envisaged as being Kurosawa-like. He tosses the badge and crosses the threshold into a new chapter.

When the screen thuds to black and the lead guitar on Ratt’s emphatic ‘Nobody Rides For Free’ slips into overdrive, that’s an all-time favourite needle drop. You’re pumped, ready to get out there and scale the impossible.

The editing is incisive and on the button, as it is throughout the whole movie. Point Break is around two hours long but it feels like 90. There is no higher praise in the cutting room. Howard E Smith, take a bow.

We end as we began, amid water. This quote from William Finnegan, author of the Pulitzer-winning memoir Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life, encapsulates the pull of the ocean which both men feel, and are affected by, in different ways.

“Everything out there was disturbingly interlaced with everything else. Waves were the playing field. They were the goal. They were the object of your deepest desire and adoration. At the same time, they were your adversary, your nemesis, even your mortal enemy. The surf was your refuge, your happy hiding place, but it was a hostile wilderness — a dynamic, indifferent world.”

The spirit of Bodhi lives on in Utah who is forever changed, and not only because he surfs every day. On the press tour in Japan, Reeves speculated on the meaning of the film from his character’s perspective. He suggested it was “a breakdown and a restructuring of a belief system, a discovery of self”.

Point Break announced Reeves as a new breed of action hero, not Speed. Earnest and minimalist, but also physical and with enough screen presence to be a leading man, even if it’s characterised more by “transfixing stillness” than theatricality. He does awe very well.

Limited in range, many say, and yet underrated. Go watch My Own Private Idaho, particularly the campfire scene. Then, 27 years later, Always Be My Maybe with Reeves as … hipster Reeves. He can flex a little.

If Utah has a father figure, it’s more likely to be his grizzled and volatile partner Pappas, played by Gary Busey. For him, the film is all about “surrendering to the moment”, which he was brilliant at on set. Cut to the stakeout at the bank. He craves a meatball sub and ad-libs the iconic line, “Utah, get me two!” Often quoted at my place.

This is by far the film I have seen most in my life but never in the cinema. So I was curious how a 4k restoration on the big screen would lift the experience. Firstly, it enhances the vivid, hazy, voyeuristic gaze of cinematographer Donald Peterman and his team along beachfront California. A few extra hues may appear in the translucent light. Bodies are aglow by a couple of extra lux.

Out to sea and deep in the surf, you can feel almost every whooshing surge of water in your face as you are swallowed whole into the belly of the ocean. There is still some grain to the print, which helps to preserve that product-of-its-time feel. A nostalgic dreaminess. Anything more might tip too far into the artificial like those upscaled videos on YouTube.

At night, figures are almost spectral, even more at the mercy of the mercurial elements. The aerial scenes now carry a more wondrous sense of the wide blue yonder as bodies glide and hurtle through the sky. Bodhi and Utah stand out better in the torrential backdrop of their climactic showdown.

But the real joy of this re-release will be the communal experience of being side by side and on the edge of your seat, hanging on every godly line and gear shift.

There are levels to Point Break. You can take it as an absurd, overblown cat-and-mouse heist movie. A hero’s journey for adrenalin junkies that soars from the crests of waves up to the heavens. Some might see heated desire conveyed in the most subtle of glances between men.

My tip is to allow yourself to get carried away. Suspend disbelief. Who cares if someone without a parachute can’t catch up with another jumper and chitchat in freefall? We’re going like a bat outta hell!

Can you tell that bankrobbers are surfers in California from a tan line and a strand of hair? Just go with it.

A real-life FBI special agent called it “one of the dumbest bank robbery movies ever made”. That’s why you never became a scriptwriter, Bill. Anyhow, Scott Spurlock did a Bodhi and made off with more than $2 million from 17 jobs … but that’s another story.

Why doesn’t Utah change his name when he goes undercover? Because he’s Johnny f&ckin’ Utah, that’s why. The name is 🔥

Point Break is my happy place and I can’t even swim 🤣

Watch and watch again. It will change your life, swear to God.

Point Break is screening from 8/11 to 21/11 as part of the BFI’s Art of Action season in London. It’s been a long road.

Elsewhere in the UK, try Picturehouses and Cineworld.

***

What are your favourite moments and memories of Point Break, 90’s kids?

Who is the biggest superfan you know?

If you’re going to see it for the first time, I envy you. Please come back and share your thoughts 🤘🏾

Thanks for the reminder, great read too. Been meaning to watch this again (tried to persuade my girl a few weeks back but she was sceptical, you have to watch it first to get it). We all need a bit of Busey in our lives don’t we! Coincidentally, I recently caught an interview with one of the world’s top surfers’ wife: her experience watching him struggle to adapt to his mundane family life every time he comes back in from riding waves the size of skyscrapers, thousand yard stare etc. Anyway, I’ll try and watch tonight.

Great fun and personable deep dive write up on one of my favourites from my teens. Amazing to get such insight and a window into the finer details of what makes it such a special film. All makes sense! Certainly more than guilty pleasure, definitely a cult classic, and without doubt an underrated masterpiece. Big respect to Director Kathryn Bigelow and ALL the cast, especially Gary Busey as Pappas - "Utah, Get Me Two!" and Tom Sizemore's cameo as DEA Agent Deets - "D'Ya Think I like this hair man!?" I must quote these two at least on a monthly basis! Dons!