For love or money?

The White Pube probes the true value of art in a 'weird textbook' of a novel

In this issue:

Headliner Poor Artists and the quest for truth

Revival Fleishman is in Trouble

Aftershow David Lynch on ideas and intuition, Kyle Chayka explains how algorithms weaken community, Eve Babitz’s adventures in Hollywood, sex miseducation in Catholic Ireland

I rarely miss an IG post from The White Pube. Gabrielle de la Puente and Zarina Muhammad are prolific, radical and relentless in pursuing a more irreverent, incisive form of art criticism. A call they felt compelled to answer when they should have been making actual art at Central St Martins around 2013.

They always say it with their chest, no apologies, and are well on the way to making revolution irresistible. They keep institutions, and the rest of us,

honest 👀 while being generous with their thoughts and inner feelings. No false objectivity here, just raw yet reasoned opinions that bite close to the bone.

On one level, it’s about forming this “mad little industry that’s sustainable, accessible, genuinely diverse, fundamentally joyful...” as Zarina wrote at the dawn of the pandemic. Beyond that, it’s placing creativity “at the heart of any new world we seek to build,” in the words of Experiments in Imagining Otherwise author Lola Olufemi.

I always learn a lot from them, about culture and not just art.

The clipping above is from Zarina’s 2021 piece What Do Critics Do? – a deep inquiry into the purpose of writing in this field. It’s important to remember that before they became de facto activists, consultants, campaigners for change – even agony aunts – they were two people trying to become better writers in this world, trying to find and articulate their voice. That’s where I connect with them mostly deeply. Their devotion to the ritual of it all and pressing the limits of language.

The critic, at their best, isn’t some snooty arbiter of taste. The best ones don’t settle for fault finding, or dwelling on what’s wrong. They make us leap beyond our imaginations towards new possibilities. On that point, track back to what Zarina wrote about fiction above – how it allows us to suspend disbelief and wonder.

After several years of hard graft and persistent inquiry, their vision has expanded into a book about the art world and not just any old straight-jacketed screed. Instead, they have given us their conception of a novel. It’s called Poor Artists and I was engrossed: in the whimsy, the idealism, the realism and the defiant struggle of it all.

We follow aspiring artist and WP amalgam Quest Talukdar from formative childhood experiences in museums and quickly feeling the urge to “speak back” through her own work, to encountering skepticism in her family and a belief that being an artist sits “outside the remit of a proper adult life”.

Later, Quest begins to find a point of view at art school, and a “shared language”, on broader philosophical questions in crits. And through encounters with practitioners and interventions from a few surreal characters like Maslow, she grapples with notions of power, capitalism, inequality and exploitation.

There is an Art King holding court as curator, feeding off his desperate subjects. There are zombies running pay-to-play exhibition schemes, trying to flog extortionate wall space to Quest as they gnaw at the flesh of a former art schooler called Royal Tunbridge Wills, who thinks he has talent. It’s a fiction but not as far-fetched as you might think.

The precarious existence of emerging artists in the UK is at the core of Poor Artists. Low income (c£12,500 pa for visual artists), steep debt, rising rents, fragile self-worth, spiralling mental health. It’s hard to make your best work when your basic human needs aren’t met and yet something compels so many of them to create anyway. To exist by their own rules, to not ask for permission to make things or tempt complicity in seeking validation through commercial success.

For Quest, she begins to realise that “Art is the only thing that can offer me something, because that’s where the beauty and optimism come in, and the clarity, and the way out of all this heavy certainty.” It’s the innate desire that makes her beg to be herself.

As the mentor-like Sheila tells Quest in her studio (a disused space and therefore temporary, of course), “Even if I’m knackered, I want to commune with the material. The communing is the art, and the rest is bullshit.” There is hope in solidarity and through an unwavering dedication to one’s practice. But these are not easy fixes. They are lifelines. [To really change things, how about offering a basic income to artists as they do in Ireland?]

Ursula K Le Guin is quoted at one point, offering a rallying cry for whoever feels at the mercy of capitalism. “Any human power can be resisted by human beings. Resistance to change often begins in art.” And rarely alone.

The authors wanted to keep readers on their toes, to get them “into this really loose state in which to imagine a better art world” as Gabrielle put it. So in addition to their own well-trodden observations on the industry and liberal sprinkles of magic realism – plenty of salt too – they folded anonymous interviews with 22 people from the art world into the narrative. Curators, teachers, technicians, Turner Prize winners, a Communist messiah…

“I realised that after years of writing, I was sick of my own opinion,” Zarina told Polyester. There’s only so many times you can rephrase cynicism toward institutions or express whatever critical thoughts I have. I really wanted to use this book as an opportunity to discover what others thought.

“I love chatting, so that was my favourite part — it was so interesting to engage with people. The conversations were fascinating because they covered both the abstract, blown-out nature of these topics and the super-specific, granular details.”

There are so many pointed observations that you could imagine someone deep in the trenches of art activism or long beholden to institutions might offer. Like this on public funding, “… galleries have to play nice, and seek to fulfil the aims of their local government’s cultural strategies. This is where the cynicism really kicks in, because it’s easy for them to dish out money to a few artists to make art about resilience, for example – make it look like they're doing something about our mental wellbeing or combatting loneliness.

“But the government uses culture to fill the holes in people’s lives, holes that have been made by the very government trying to half-heartedly fill them back in.” Zing.

Or this on collaboration as exploitation: “It’s not that I think people shouldn’t work together. It’s more that the literal production of art is kept in the shadows and that is disingenuous. It upholds the notion that the artist did the thing on their own so the artwork belongs only to them; they are the singular genius in a world where ideas are more valuable than the labour it takes to bring those ideas to life.”

Some of the accounts they heard were quite bleak. Time and again, artists are asked to lean too heavily on their purpose or resilience. Yes, something can be forged in the fire, but to read about a person having to secretly sleep in their studio amid a housing crisis and piss into a bucket is a shameful indictment of the status quo. “That we would have to put our bodies through such stress and discomfort to hold on to the thing that we want to do,” Gabrielle told Dazed.

As a piece of long-form writing, Poor Artists is a triumph. A book with a unique form that plays off the tension between romanticism and indignation, combining fiction and journalism in a fresh and provocative manner.

Taking up the challenge from one of their editors to create a “weird textbook”, but with a sharpness, the authors collaborated from different cities, going back and forth to try and find a third voice that could fuse Zarina’s element of surprise with Gabrielle’s clarity of expression.

Bear in mind, they also had to maintain The White Pube website with its weekly texts, funding library and grant programme. And Gabrielle has been dealing with POTS after getting Long COVID in 2021.

Success is subjective and it’s easy to overplay how well someone is doing from afar. Getting a book published does not mean you are rolling in it. But to complete a significant piece of work and share it with the world in these circumstances is a major achievement, however many copies are sold. An act of will that will revive weary souls and encourage them to hold their ground.

Quest is naive and earnest, which is a useful place to write from. She goes on quite a journey, from thinking that '“being an artist must be a really important role that the whole world takes very seriously,” to fearing that art is “an opportunistic industry built around something that used to be sincere”.

And yet Quest feels this gravitational force pulling her into the fray. Poor Artists is frequently in undeniable awe of creation and invested with an anarchic spirit that feels necessary right now. An enduring compulsion to make art for art’s sake, in community with each other. To stay true to oneself.

PS In the Acknowledgments we are told that Gabrielle and Zarina got a meeting with publisher Penguin after crossing paths with agent Milly Reilly on the same train to a conference in Germany. That speaking opportunity only came because they developed a paying readership through Patreon, which also led to a lecture at Chelsea College of Art in 2018.

Among those in attendance was Emmy Yoneda, who would later champion Poor Artists as an Assistant Editor. So good things can happen if you put yourself out there and say hello. Make friends, not contacts. We can help each other rise from the ground up.

Forthcoming Poor Artists events

Fleishman is in Trouble

As A Real Pain, Jesse Eisenberg’s new movie with Kieran Culkin, is doing the rounds, I thought it would be worth revisiting one of his more overlooked roles in a TV adaptation of Taffy Brodesser-Akner’s first book.

As neither a father nor a spouse, I was curious about what drew me to Fleishman is in Trouble not once but twice. The Hulu Original was adapted from a novel by Taffy Brodesser-Akner, whose NYT profiles of stars such as Val Kilmer have become the effusive gold standard. It appears to centre on pious Dr Toby Fleishman (Jesse Eisenberg) who is struggling to deal with his divorce from Rachel (Claire Danes), a status-obsessed, workaholic talent agent.

They were a financially secure couple ensconced in a Manhattan milieu where everyone's trying to outdo their 'friends' and compete for the title of most unlikeable or obnoxious. Now Rachel's taken off somewhere (not alone), leaving the kids with Toby who's been tearing through the dating apps like a horny college kid fresh onto campus.

David Lynch – just “catching ideas” 🕊

It’s always crushing when an ever-present artist with decades of still-mesmerising work leaves us. But the tributes to lovable eccentric David Lynch have been a joy. In such moments, I always take a step back and consider how deeply one person can affect millions through dedication to craft, conviction and an eagerness to “deepen the mystery” as Francis Bacon put it. (Aka being human.)

Lynch was so confounding that he earned his own adjective – Lynchian – as if one word could articulate the foreboding, beckoning strangeness of what we had just experienced.

Talk show host Charlie Rose asked him what it meant almost thirty years ago. “I haven’t got a clue,” Lynch replied. “I think that when you’re in it, you can’t see it.”

My first Lynchian experience was Twin Peaks in the 90s, which is still the apex of immersive TV in my life. How we were drip-fed one non-sequitur of an episode after another each week and spent the next day speculating about it at school.

There was no internet to consult in quiet moments in your room. Just you and your subconscious. I still get shivers thinking about every time Bob appeared and can’t wait to watch the show again. All three series including that unlikely return in 2017.

Then came Wild at Heart with Nicolas Cage and Laura Dern, a “road movie” about a hot young couple on the run “finding love in hell”. It has its own volatility and a dark schizophrenic tone, careening from gruesome to melodramatic as they try to evade a despicable cast of oddballs. From that point on I was hooked and Lynch became a name to follow into the void.

Like all the best artists, he saw things most others could not. Collaborators Kyle MacLachlan (Dune, Blue Velvet, Twin Peaks) and Naomi Watts (Mulholland Drive) said as much in their tributes the other day, how Lynch’s faith in them gave each actor the confidence to grow.

He noticed things. This is the guy who used to live opposite a morgue in Philadelphia and remembered seeing the body bags behind cleaned out with hoses. “With the zipper open and the bags sagging on the pegs, it looked like these big smiles,” he said. “I called them the smiling bags of death.” If there’s a liminal space between the macabre and the mundane, he owns it in perpetuity.

Lynch’s creativity went far beyond film. He started out as a painter but after an epiphany one night he wanted to make those paintings “move”.

Lynch loved photography, taking pictures of naked bodies, insects, snowmen, smoke… His black and white series on factories is a personal favourite. Eerie, unsettling and melancholic.

There was sculpture.

As far back as 1977, he was experimenting with sound, producing the score for his first film Eraserhead with Alan Splet. Many more releases followed including this billowing aural sidestream of a collaboration with Chrystabell.

The noir blues of ‘Ghost of Love’, from Inland Empire in 2006, is giving major Lynch as I type this.

Not disturbing enough for you? Then try ‘Crazy Clown Time’.

Anyone who has seen a candy-coloured Dean Stockwell mouth Roy Orbison into a prop light in Blue Velvet knows this man was a genius at conceiving musical moments in cinema.

“Music can say intellectual things but it can also speak to the heart in a wordless way that’s so powerful,” he said. When not making the music he was directing it, as this all-time classic clip with Twin Peaks composer Angelo Badalamenti bears out so majestically. “Slower, David?”

Let’s not forget he was also a compelling character in front of the camera too. Apart from Twin Peaks, I would recommend Lucky where Lynch plays curmudgeonly loner Harry Dean Stanton’s best friend Howard. FYI, Howard’s best friend is a tortoise. Need I say more?

I last watched Lynch in Steven Spielberg’s semi-autobiographical The Fabelmans as cigar-smoking director John Ford. A tall exclamation mark on his acting career. “Now get the f*ck outta my office!”

Nicolas Cage/”Nickster” remembers how Lynch had a “joyful sense of humour”. Intentional or otherwise, he was very funny. Whether it was revealing quirks in interviews with zero self-consciousness, forecasting the weather for years (“You have a good day” 😎) or refusing to elaborate on why Eraserhead is his “most spiritual film”.

Indeed, he was a big proponent of intuition and leaving things open to interpretation.

“I like a story that has some concrete structure but also holds some abstractions. Life is full of abstractions and the way we make head or tail of it is through intuition. People get used to a film that pretty much explains itself 100% and they kind of turn off that beautiful thing intuition. Some people on the other hand love these abstractions. It gives them room to dream. An abstraction, to me, is something that cinema can say.”

Lynch became something of a guru to aspiring artists who were keen to unlock their ideas with similar freedom and fluidity. Transcendental meditation underpinned his creative process, which he began in 1973 and practised twice a day, every day, until the end of his life. Many have followed.

He described it as “a mental technique that allows any human being to dive within … and experience the source of everything.”

But what if you only have one idea and you’re afraid it won’t work out? “That’s the most critical one,” Lynch said in 2006. “Then I say it’s like bait in fishing. That idea, if you focus on it, will draw other ideas in. And like fishing, you have to have patience. You don’t know how long it will take but if you keep focusing on it, and wiggle the line a little bit, it’ll bring ‘em in.”

David Lynch made peculiar a virtue and elusive a badge of honour. We need more supersentient human beings like him making art, peering behind the red curtain and daring us to cross the threshold into the unknown.

What are your favourite memories, moments or facts about him?

Final thought: Lynch had one of the coolest cuts on the planet and makes me want to wear my greys with pride. Give me the Lynch, barber!

Derrick Gee interview with Filterworld author Kyle Chayka on algorithmic culture and gatekeeping

This was an excellent conversation between Derrick Gee and Kyle Chayka (New Yorker staff writer and author of Filterworld) on discovery, tastemaking, gatekeeping and finding meaning in digital culture.

Here is the crux for me, where Kyle talks about how algorithms thwart the development of real community.

“There is a curation element that absolutely persists on the internet. Where you have really interesting people with unique perspectives bringing their voice to more and more people. But where I see the influence of the algorithmic feed is that community can’t be built if everything is changing all the time.

“Like if you just expect to be swept in and out on the algorithmic tide you don’t stay long enough, you don’t invest long enough to be part of a community. You just rely on it coming back to you passively. So I think that’s against community in a way.”

That’s Substack' Notes for me, Instagram Stories and a whole lot more.

Where do you feel the strongest sense of community in your life? What do you get from it?

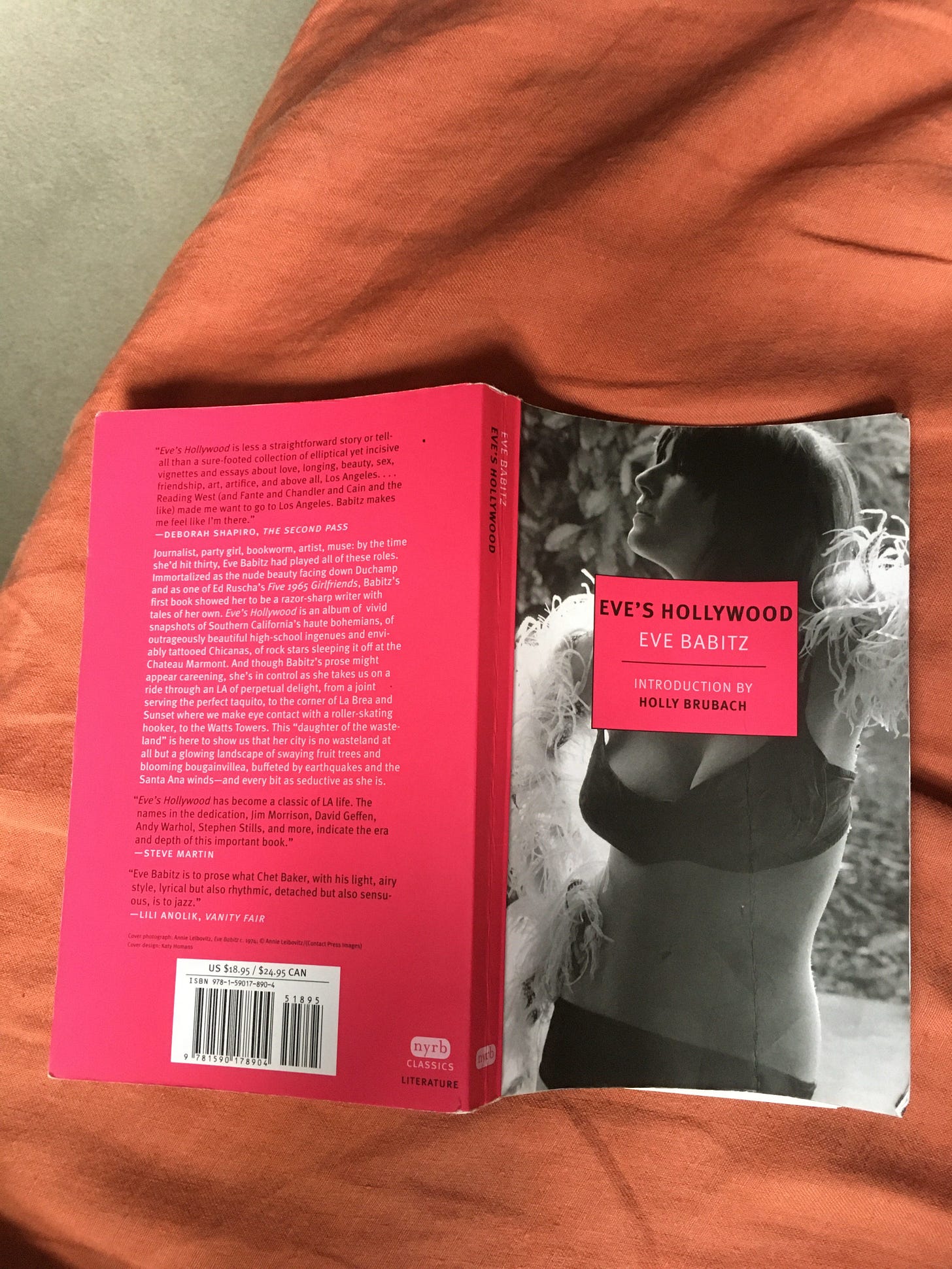

Eve’s Hollywood by Eve Babitz

This collection just got better and better. Eve’s antics and conquests overshadowed her literary prowess. But she could really write, and in a style unlike anyone else. Transposing her voracious, freewheeling spirit onto the page in sassy, dreamy and compulsive prose. Simultaneously awonder in the moment at yet with a knowingness that could only have formed over time.

Demystifying LA’s allure, reminiscing about old flames, musing on Cary Grant and Marlon Brando, introducing Frank Zappa to Salvador Dali, sharing eventful chapters in New York and Rome, craving taquitos on Almeda off Sunset with extra sauce dripping all over… I wanted to hear about it all from Eve.

Recalling ingenue best friends of the past –

“Because Sally was so quiet, hardly anyone saw her at first. I also think it was because she willed herself to disappear that the sorority sisters who sometimes made an exception and rushed a newcomer in the 11th grade forgot to look at her. With me, she came dramatically into focus on the third day because I saw her smile and her smile from that Garbo sadness broke the heavens open in choral arpeggios and the guy sitting next to me just sat there after she’d gone past. Just sat there.”

Meeting a boyfriend’s evil mother –

“ … and the closest I ever got to that feeling of Westwood was when someone took me out of the Lower East Side in New York one horrible summer day to their mother’s house in Westport, Conn., and their mother was so shocked and repelled by me (she could tell I was Jewish, where her son hadn’t noticed) that she ran slides of his ex-girlfriend for 45 minutes after dinner. That’s what Westwood is like. You could slam its teeth down its throat.”

Are you a fan? What should I read next? Black Swans, maybe.

Sex Education for Girls @ in The Press, Hypha Studios

I was transfixed by Ciana Taylor’s video installation Sex Education For Girls, my highlight at a show called In The Press, which is on until 29 January in Mayfair. It’s a fever dream about intimacy, ‘love’, shame and the tyranny of the Catholic church, built around a real-life 80’s sex ed video.

When this lady said “That is all”, it spoke volumes. What’s all the fuss? Here is a two-minute edit but you should see the full version, on an old TV that’s perched on a wooden chair.

In the Press features a group of 11 multidisciplinary artists with a strong connection to Ireland – as a place of birth, home or work. The show is curated by Hazel O’Sullivan & Ciarán Mac Domhnaill.

Props to Hypha Studios for making shows like this possible by connecting artists with vacant spaces to host exhibitions for free.