Bean and gone 😋

How mum made a kitchen cupboard staple feel special

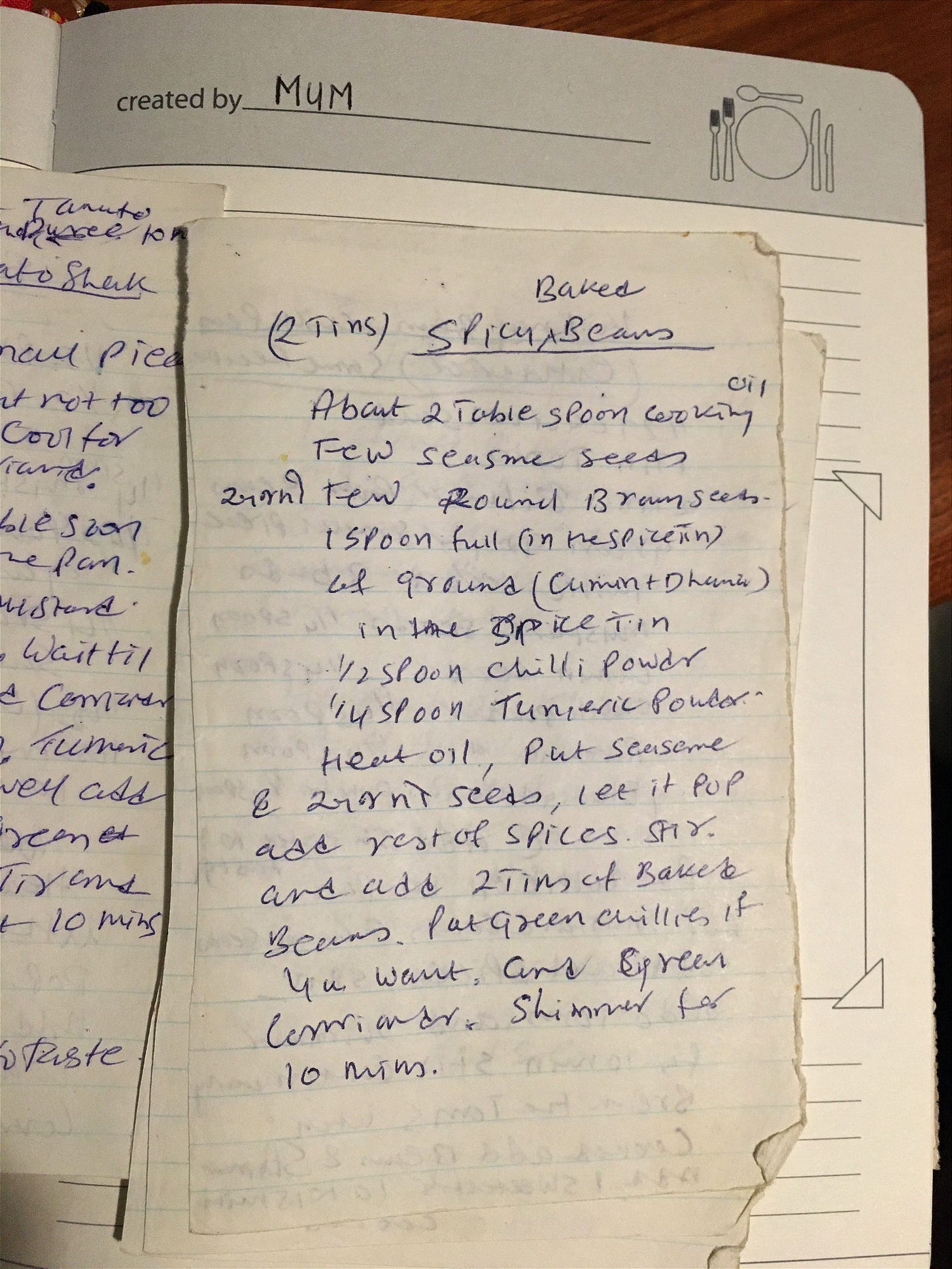

One of my most prized possessions is falling to pieces. A red A7, paperback notebook. The kind that cashiers might have scribbled numbers in during the 80s. Or pupils and their new vocabulary, if you went to my prep school.

But for my mum, it was where she kept family secrets in the form of fabled recipes scrawled on lined paper. Illegibly, I’d add, as if anyone fortunate enough to stumble upon it would have to crack a code, even her own flesh and blood.

Inside, a buffet of gorged-upon Gujarati dishes – by way of Uganda – that she served for years including spinach bhaji [what others might call dal shaak]. A very tomato-y bateta nu shaak [which I dubbed “Red shaak” when I requested it with a cheeky grin].

And how could I forget makai nu shaak, the most unique and satiating combination of sweet, spicy and creamy… As her chief taster, I got to know all these signature specials extremely well.

There were two of these booklets, in fact. The second one was made for me to take to university in Leicester. How else would I survive without a taste of home every week, without mum’s nourishment from afar? Children of fretting South Asian mothers will relate here. Or could it have been that the real assignment was to spread her legend all across the Midlands?

Braindead flatmates later threw away this copy in London around the time she became seriously ill in 2011. Dad found the other one among her possessions around a year after she passed. I wept. That was my cue to take up the baton again and relive memories by the plateful, in the very same kitchen she had worked her magic.

Mum was always on a mission to feed and fill the family, not to mention countless friends and colleagues of mine through the years. As I say to people whenever we roll out of some overhyped must-eaterie in the capital, these places don’t know how to put food on the plate – not like my old dear.

Her crispy, golden pea kachori and squidgy dhokla went down particularly well, enriched with just the right measure of heat to warm hearts, lift spirits and earn repeated invitations to offices from Redhill to Primrose Hill.

South Asian cooks will have their own interpretations of all these dishes. But if I had to describe what made my mum’s food stand out, it was her inimitable balance of sugar to spice.

Her cooking was almost always vegetarian, often mild but seldom bland. Imparted through conversation down the generations, to be remembered rather than written out. There’s a subtle alchemy at play. So much so that, even if I follow these recipes to the letter and number, they just don’t quite taste the same. They never do, right.

I used to joke that one of the best restaurants in Brighton was at home on Wayland Ave, open only to VIPs. There she would cook with great versatility, frugality and intuitiveness. Her repertoire extending to moreish interpretations of classic fare such as saucy sausages and bacon, latticed potato pie and turkey casserole that I would ladle onto my plate and devour with basmati nice and naan bread.

You see, her ‘fusion’ was expedient and unpretentious – a way to maximise what was in the house, tweaking on instinct and flying by the seat of her tastebuds. I can see mum now, her osteoporosis-formed figure hunched over the stove as she samples everything several times, adding a little more salt or water, or pulling out the spice tin again to fine-tune.

For more than two decades my parents worked in newsagencies seven days a week. Thursday was cash and carry night, when they finished unloading around 10.30pm. My brother and I would help – yes, on a school night. (I was delivering newspapers at eight years old, but that’s another tale.)

In situations like that, she didn’t have the time to spend hours slow-cooking meals (aside from moong dal in the pressure cooker on Sunday afternoons) or experimenting with wild takes on trending tastes like some proto-food blogger.

But during a house clearout, I did discover a drawer full of tatty clippings from newspapers and magazines that she would read in the shop. Delia’s in there, Keith Floyd too, even a young Nigella, introducing the nation to flavours from abroad. So she was also willing to stretch out and play with classic cuisine from the UK, Italy and beyond. To embrace other cultures in the kitchen and … blend in.

Perhaps the best example of mum making something her own is also one of her most humble dishes. Spicy beans … and it certainly does what it says on the tin. When I think of ‘baked beans’, my first thought isn’t Heinz, Branston or some other brand. It’s the tangy, tingling sensation of chilli, coriander, earthy turmeric and slightly bitter cumin working its way from the tip of my tongue to my tonsils and settling in my stomach like a weary soul into his favourite armchair.

It's an edible manifestation of diaspora – what it means to make home elsewhere, then adopt and adapt traditions. A reincarnation of an everyday pleasure. A comfort food that I have enjoyed in different contexts, from breakfast time as a little boy beside a plate of scrambled eggs, to dinner just last week smothered over a crispy jacket potato and topped with crunchy extra mature cheddar.

In a way, her interpretation is quite apt for a food that has long been perceived as British classic and yet contains a type of haricot bean that originates from the Americas. Navy beans could be found in earthenware dishes baked by tribes including Iroquois, Narragansett and Penobscot, sweetened with maple syrup and often bolstered by red meat.

Heinz, the first brand I tried in our shop, imports more than 50,000 tonnes of them every day, taking a shipment at its factory in Wigan from North America via Liverpool’s docks.

There are many versions of these root recipes in New England states today including lumberjack essential bean-hole beans, which were first cooked in the ground using earthenware pots in the 19th Century and contained the yellow-eye variety of legume among others.

As different communities settled in the state they made it their own, swapping different core ingredients like maple syrup or venison for molasses and salt pork. That’s how Boston baked beans came about.

Consider also the influence of the French cassoulet, which dates back to the 1400s. From its roots in the farmhouses of Languedoc in the southwest, this stewed variety has been adapted in several ways over the centuries. For instance, in Carcassonne they added mutton and partridge to a base of pork, ham, garlic, onion, tomatoes, herb and stock. Now that’s putting food on the table.

Did you know that baked beans used to be considered a luxury? At Fortnum & Mason in 1886 anyway, when the upmarket department store began stocking Heinz in limited quantities. When rationing hit Britain in the Second World War, they removed pork from their recipe. A very utilitarian formulation of a dish that endures to this day. Its ingredients still a secret.

A person in the UK consumes just under 5kg of baked beans every year. Heinz is still the best-selling baked beans brand in an ever more crowded market, though not necessarily the best-tasting (Aldi, take a bow). And the company exports to more than 20 countries. So their legend lives on, forever tinkered with and repackaged.

It feels like baked beans belong to everyone and no one. Their familiarity and ubiquity makes them the ultimate comfort food and quick snack, ripe for adoption and reinvention. But you have to switch it up to keep it interesting.

Mum was never that brand loyal when it came to either selling them in the shop or reinventing them in the kitchen. She knew how to take any old can and pepper it with a pungency that tastes like home.

SPICY BAKED BEANS

Ingredients

2 tins baked beans

2 tbsp vegetable oil or an alternative such as Carotino

1 tbsp tomato puree

½ tsp sesame seeds

½ tsp brown mustard seeds

1 tsp cumin powder

1 tsp ground coriander

½ tsp chilli powder

½ tsp turmeric powder

1 medium green chilli (finely chopped)

Small handful of fresh coriander (chopped)

Salt and pepper to taste

A pinch of brown sugar

Method

1. Gently heat the oil in a saucepan.

2. Add the brown mustard seeds and sesame seeds.

3. When the mustard seeds start to pop, add the spices and stir (tempered and freshly ground before adding oil, if you want to take it to the next level). Any excuse to pull out the pestle and mortar.

4. Add the tomato puree and continue stirring.

5. Pour in the baked beans and combine with the spice base.

6. Add the chopped green chilli and fresh coriander and simmer everything for 10 minutes.

7. Season and serve.

Notes

Heat the spices gently to retain all that invigorating flavour. A little patience will pay off at the end.

As mentioned above, these beans go so well on a crispy yet fluffy jacket potato, topped with an avalanche of extra mature cheese.

But you can also switch up your breakfast plate, baking them for real this time with eggs, topped with a sprinkle of paprika and sumac and served with naan and ketchup. It’s what we do 💁🏽♂️

I know Dishoom’s Masala Beans have many fans but the onions don’t really add much for me. Their texture takes away from the pleasing simplicity of just beans, sauce and coriander leaves rolling around my mouth. And it takes longer to cook.

Similarly, I’ve seen lots of recipes where a couple of cloves of minced garlic are added after the oil and before the spice blend. To add depth of flavour or more aroma, I assume. To make it more ‘buttery’. If that sounds appealing, why not experiment? I think there’s enough going on.

How do you like your beans?

Which mum recipes do you reach for when you want a taste of home?

What’s the first dish that comes to mind when you think of your childhood?